Some places vanish all at once. Others disappear more slowly, like a ship slipping beneath the water, there one moment, then gone, leaving only ripples. Tahawus, New York, did both. Born of iron, sustained by titanium, it stood as ruins for years. Now, it’s gone. But beneath its silence lies the story of a village that devoured itself to stay alive.

Long before this rugged corner of the Adirondacks appeared on maps, it held a different meaning. For the Mohawk, Oneida, and Mahican peoples, the high peaks weren’t obstacles or resources to be extracted, they were part of a living landscape, governed by seasonal rhythms. The river valleys fed game trails, and the forests offered not just shelter, but medicines, stories, and ceremony. These mountains weren’t home in the modern sense of permanent settlement, but they were deeply known. Every ridge, every stream had a name, a purpose, a memory attached.

What would one day be called Tahawus sat within a vast expanse governed by the Indigenous principle of collective stewardship, what the Haudenosaunee called the “Dish with One Spoon.” It was a covenant of restraint and respect: one bowl, one spoon, shared by many. No one took more than their share, and all had a responsibility to care for the land so it could continue to provide for future generations.

This wasn’t ownership in the European sense. There were no fences, no titles, no deeds. But there was belonging. Deep, reciprocal belonging. The Adirondack interior may have seemed wild and empty to the first industrialists, but that perception came from a failure to see the land through Indigenous eyes. The absence of permanent towns wasn’t absence at all, it was balance. Movement was intentional. Presence was seasonal. And the land was never without meaning.

That balance, though, would not last. Where the Haudenosaunee saw shared sustenance, the next wave of visitors saw untapped wealth. Mountains once approached with reverence were now approached with surveyor’s tools and profit margins. The land that had been walked gently for generations would be carved, blasted, and burned in the name of extraction.

The “Dish with One Spoon” gave way to the furnace and the smokestack. What had once been guided by seasonal migration and mutual care became fixed, fenced, and claimed. Iron didn’t ask permission, it demanded domination. The same forests that once sheltered migratory hunting camps now fed charcoal kilns. Rivers were dammed. Earth was torn. Permanence, long avoided out of respect, was forced upon a land that had never needed it.

In that rupture, Tahawus was born.

The name “Tahawus,” long believed to be an authentic Native American word meaning “Cloudsplitter,” carries with it the strange alchemy of myth and reinvention. In truth, it was coined not by Indigenous people but by a 19th-century poet, Charles Fenno Hoffman, who romanticized the region and, like many of his era, projected a noble mystique onto the landscape by inventing Native-sounding names that echoed with imagined wildness.

Despite its fabricated origin, the word stuck. It sounded ancient, powerful, and rooted, so it became all those things. It attached itself to the mountains, to the club, to the mine, to the memory of the place. Like the iron buried deep in the mountain’s bones, the name was forged into identity. It became shorthand for grandeur, for wilderness, for resilience, and later, for disappearance.

In a way, the name itself is a kind of artifact, a constructed story mistaken for something older and truer. It mirrors the arc of the village it came to define: a place that reshaped the land, then vanished into it. Tahawus was never a Native village, but the name gave it the illusion of timelessness. An illusion that endured, even as the town built on it did not.

In 1826, guided by Elijah Benedict, believed to be of Abenaki descent, industrialist David Henderson was led to a rich deposit of iron ore in the heart of the Adirondacks. Henderson and Archibald McIntyre established the Adirondack Iron Works, and by 1827, a company town took root. Called McIntyre, later renamed Adirondac, the village was a marvel of remote ambition: blast furnaces, kilns, mills, farms, and homes carved out of wilderness.

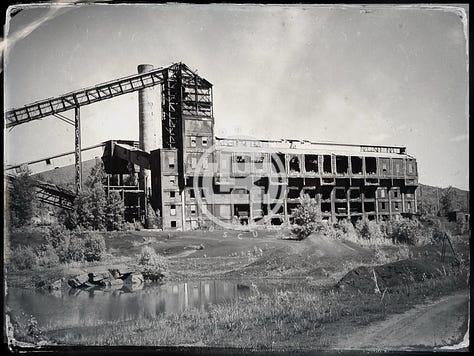

At its peak, more than 400 men lived and labored in this deep forest factory. They smelted ore, built dams, and fed an industrial dream. But the ore had a secret: it was laced with titanium dioxide, stubborn and impure by 19th-century standards. Without a railroad, shipments crawled. Without Henderson, killed in a freak gun accident in 1845, the enterprise floundered. The Panic of 1857 and a catastrophic flood sealed its fate. By 1858, the furnaces went cold. The town emptied. Adirondac became a ghost.

Then came the hunters.

In the late 1800s, wealthy sportsmen discovered the abandoned village. They turned industrial ruins into rustic lodges, stocked the lakes with fish, and renamed the settlement once again: Tahawus. The Tahawus Club was part of a broader trend, a Gilded Age obsession with wilderness recreation. Its guests included captains of industry and politics. One of them was Theodore Roosevelt.

In September 1901, Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was staying at the MacNaughton Cottage in Tahawus with his family. He had returned to the Adirondacks after earlier visiting President McKinley in Buffalo, where the President had initially appeared to recover from an assassination attempt. Confident that McKinley would survive, Roosevelt resumed his vacation in the mountains.

That changed on September 13, when a messenger arrived with urgent news: McKinley’s condition had worsened dramatically. Gangrene had set in, and the President was not expected to survive the night. Roosevelt left immediately.

He descended from the area near Mount Marcy and traveled by horseback and carriage over roughly 35 miles of rough road to the train station in North Creek. The route was long and slow, cutting through dense forest with little lighting or infrastructure. When he arrived in the early morning hours of September 14, a telegram was waiting at the station: President McKinley had died at 2:15 a.m.

Roosevelt boarded a train to Buffalo later that morning, where he was sworn in as the 26th President of the United States at the Ansley Wilcox House.

The moment marked one of the most unusual and remote presidential transitions in American history. It began not in Washington, but in a quiet Adirondack village, a former iron town turned private retreat. Tahawus, once built to extract value from the land, had, for a brief moment, become the starting point for a new presidency.

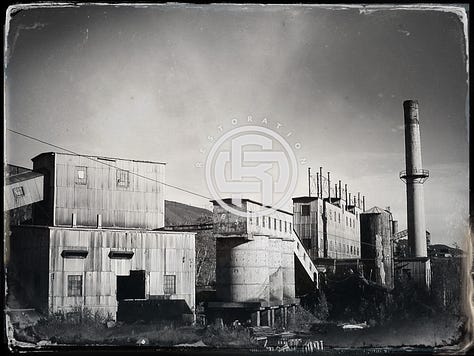

The third life of Tahawus began with war.

In the 1940s, National Lead Industries returned. The same titanium dioxide that once doomed iron now had strategic value. Used in military paints and smokescreens, titanium became essential during World War II. The government backed the effort. A railroad was built. The ghost town was leveled.

A new village, modern Tahawus, rose nearby. It had homes, a general store, a schoolhouse, and even an internal publication reportedly titled The Cloudsplitter, a name that echoed through each generation of the site. Its residents were diverse: immigrants from Europe, South America, Asia, and beyond. They carved a life from the mountain, building a self-contained community deep in the woods. In a strange twist, the land that once resisted iron now surrendered titanium.

But the mountain would consume the village again.

In 1963, geologists confirmed a rich vein of titanium lay directly beneath the town. Rather than halt mining, the solution was simple: move it. Homes were loaded onto flatbeds and hauled 15 miles to Newcomb. The people stayed, but the place did not. Once again, Tahawus vanished.

Mining slowed in the 1980s. Demand dropped. The railroad stopped. On Thanksgiving Day 1989, the last ore train left the site. And with it, the final breath of a company town.

Today, the land lies quiet. The pits are flooded. The furnaces are cold. Trees reclaim the tailings. But history hasn’t let go. The McIntyre Furnace still stands. The MacNaughton Cottage still draws visitors. The trailheads bustle with hikers. The Open Space Institute and the DEC now manage the land, balancing legacy and renewal. Mitchell Stone Products continues to mine the old tailings for aggregate, the leftover bones of a mining giant, ground down for roads and construction.

Tahawus remains a living ruin, layered with memory. A place that rose and fell with shifting definitions of value. Where the unwanted became essential. Where a village was built, erased, rebuilt, and erased again.

Some ghost towns are abandoned. Tahawus was devoured.

And that, perhaps, is what makes it unforgettable.

I last visited the full Tahawus complex in the late summer of 2004. One of those Adirondack days where the sky is an unbroken pane of blue. The sun warmed the buildings, but the night still lingered in the corners, cool, still, like breath held too long.

The place felt more evacuated than abandoned. Timecards lay scattered in the guard tower, some half-filled, others blank, as if a final shift had ended and never resumed. Tools remained on the benches in the shop. It wasn’t a ruin, it was a freeze-frame. I had stumbled into the last day of a town, suspended in air, left for the elements to archive.

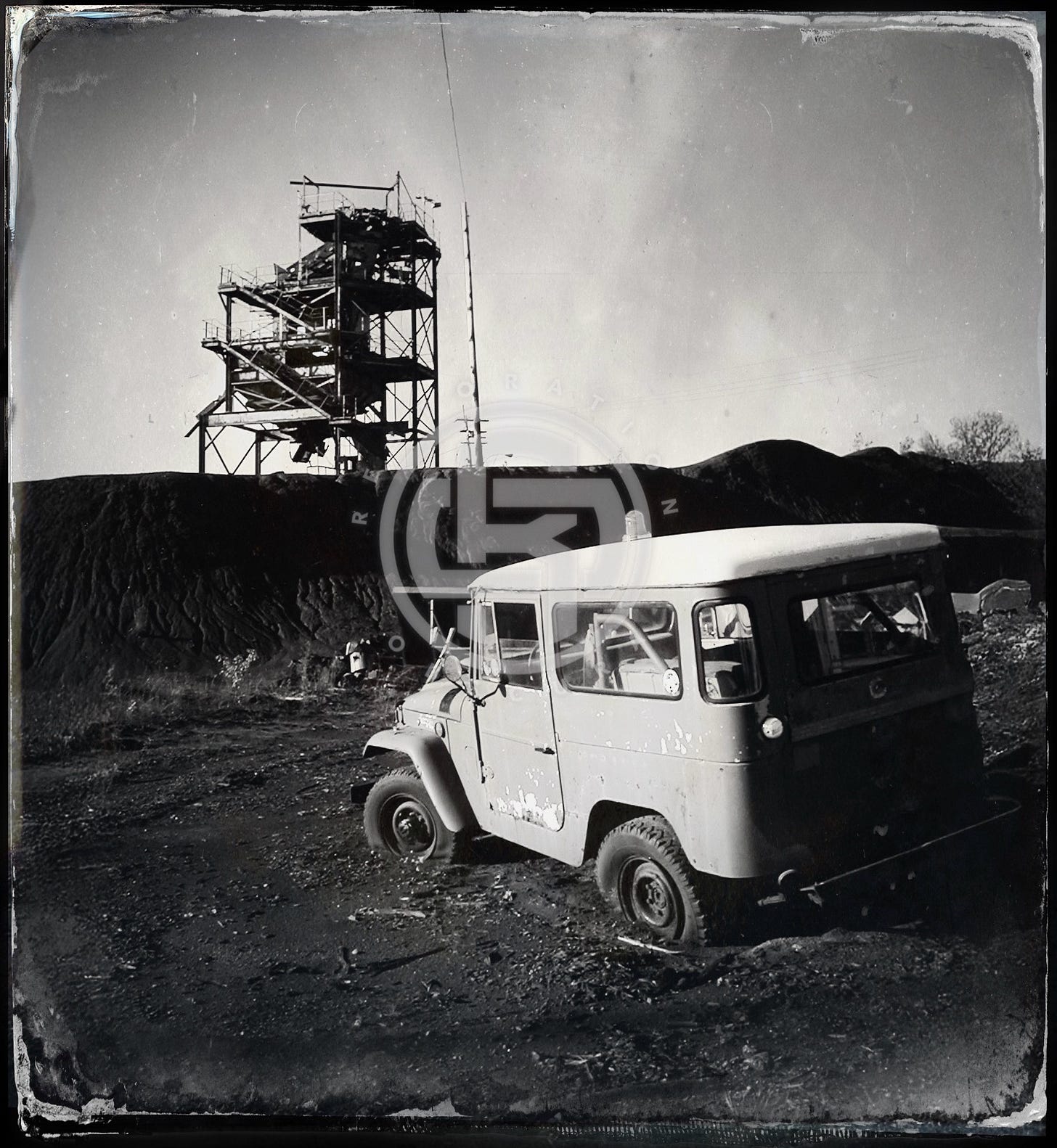

There was an airstrip, its faded lines nearly lost to creeping weeds. The infirmary stood with cabinet doors ajar, instruments rusted but intact. Thousands of square feet of empty industrial space stretched around me. Conveyors sat silent. Cranes rested like sleeping animals. Platforms tethered by thick cables stood like grounded spacecraft, strange and angular. Old Army-green Jeeps lay half-sunk in black soil, their hoods overtaken by moss. And everywhere: tailings. Mounds of waste rock, stacked so high and sterile they resembled craters from some forgotten war. The entire site felt like a moonscape had been dropped into the heart of the Adirondacks, alien and stark, ringed by trees that didn’t quite know what to make of it.

At the edge of the site stood the smelter. Enormous. Black. Empty. It didn’t look like a machine, it looked like the ribcage of a long-dead monster. You couldn’t help but feel small beneath it. Like you were standing inside something that had once lived and breathed industry.

And in the middle of it all was something I had never seen in the Adirondacks: a large, holding reservoir filled with the clearest turquoise water I’ve ever encountered. It lacked the tannins that stain most Adirondack water that deep amber brown. This was crystal. Water pulled from the fractured watertable, undisturbed.

And at the bottom of that pool was a forest. Still standing. Whole trees, upright, branches intact, as if waiting for the thaw. It didn’t look flooded. It looked paused.

I took photographs of everything I could find. Every hinge. Every cable. Every warning sign rusted into unintelligibility. I knew this place wouldn’t last. Not like this. It was too intact, too perfect. History doesn’t let places like this stand. Not because of weather. But because of liability. Because of memory. Because someone always comes to clean up what they don’t want remembered.

Tahawus wasn’t fading. It was waiting to be dismantled. And I had arrived just in time to see what was left.

Postscript: The Silence That Remains

In all my wanderings, whether in the deep woods of the Adirondacks or among the sun-bleached planks of a mining town in Aruba, I’ve found that abandoned places seem to share the same air. Not just the same smell, but the same dry warmth, the same stillness. It’s like the place is holding its breath. Like it’s waiting for you to leave so it can quietly go back to unraveling.

There’s a word for that feeling: kenopsia, the strange, haunting stillness of places once full of life. But it’s more than a mood. It’s a kind of presence. A place made for people always feels a little wrong when it’s empty. Like a school after the last bell. Like a theater with the lights still burning after the actors have left.

These places don’t just feel empty. They feel paused, like the story got cut off mid-sentence.

Kenopsia isn’t about mystery. It’s about memory made physical.

It’s the weight of absence in a place built for presence. Dust settling on things once in constant use. These spaces feel full, even when they’re empty, shaped by the patterns of lives that unfolded there. What lingers isn’t spirit or myth, but the quiet architecture of routine.

When I photograph these places, I’m chasing questions. Why here? Why this layout? What made this spot worth building on, working in, raising families around, and then, eventually, walking away from?

Tahawus has all of that. The industrial skeleton. The layers of memory. The erasure you can still see. It’s not just what was, it’s what might have been. And that’s what stays with me.

Each place I visit adds to a kind of personal map. Not one of geography, but of memory. Over time, I’ve stopped just seeing what people built, I’ve started trying to understand what they believed. What promises did this town make? What did people hope for when they came here? And what did they carry with them when they left?

Tahawus feels like a turning point in that search. A place that doesn’t just tell a story, it holds a mirror up to the bigger ones. About what we value. What we sacrifice. And how little say we really have when the land decides it’s done with us.

After years of walking through these quiet places, I’ve come to believe we’re drawn to ruins not just because they’re forgotten, but because they help us remember. They show us how temporary even our biggest efforts are. How everything we build is, in some way, borrowed.

Tahawus doesn’t preach. It just stands there, letting the trees take it back inch by inch. It teaches that usefulness is fleeting. That permanence is a kind of myth. And that silence, sometimes, tells the most honest story of all.

It reminds me that in chasing permanence, we leave behind beautiful, accidental evidence of our impermanence, and that’s something worth honoring.

Episode 3 of the Restoration Obscura Field Guide Podcast is out now.

Beneath the Berkshires, a nearly five-mile tunnel cuts through Hoosac Mountain, a staggering feat of 19th-century engineering known formally as the Hoosac Tunnel. But those who know its story call it something else: The Bloody Pit.

In Episode 3, we explore the violent, haunted history of this infamous tunnel—an industrial colossus forged with hand tools, black powder, and the lives of hundreds of men. From the catastrophic collapse of the Central Shaft in 1867 to reports of phantom figures and unexplained lights, this isn’t just a story about trains, it’s about memory, ambition, and the steep price of progress.

We also draw connections to other forgotten places like the erased mining town of Tahawus, where industry once thrived in the wilderness, and where the past still shows through if you know where to look.

Listen now on all major streaming platforms or directly on Restoration Obscura:

https://restorationobscura.substack.com/p/the-bloody-pit

About Restoration Obscura

Restoration Obscura is where overlooked history gets another shot at being seen, heard, and understood. Through long-form storytelling, archival research, and photographic restoration, we recover the forgotten chapters, the ones buried in basements, fading in family albums, or sealed behind locked doors.

The name nods to the camera obscura, an early photographic device that captured light in a darkened chamber. Restoration Obscura flips that idea, pulling stories out of darkness and casting light on what history left behind.

This project uncovers what textbooks miss: Cold War secrets, vanished neighborhoods, wartime experiments, strange ruins, lost towns, and the people tied to them. Each episode, article, or image rebuilds a fractured past and brings it back into focus, one story at a time.

If you believe memory is worth preserving, if you’ve ever felt something standing at the edge of a ruin or holding an old photograph, this space is for you.

Subscribe to support independent, reader-funded storytelling: www.restorationobscura.com

The Restoration Obscura Field Guide Podcast is streaming now on all major streaming platforms.

Every photo has a story. And every story connects us.

© 2025 John Bulmer Media & Restoration Obscura. All rights reserved. Educational use only.

Permissions Statement

Restoration Obscura may not hold copyright for all images featured in its archives or publications. For uses beyond educational or non-commercial purposes, please contact the institution or original source that provided the image.

Having attended many of the Cabin Fever Sundays at the Adirondack Museum, I recall it being said that the McIntyre blast furnace was fired only once but a firing (blast?) lasted for quite a long time. Is my memory flawed?