Lake George is a place of postcard beauty—sunlight on still water, tourists crowding the docks, families paddling into summer memory. But beneath the surface lies something older and darker. For more than 250 years, this lake has swallowed ships. Warships, steamboats, and private vessels now rest in the cold, silent deep—preserved in near-perfect condition by the lake’s unique chemistry. What looks like a vacation destination is also a graveyard. This is the true story of the ships that never came home.

These aren’t myths.

Beneath the pristine surface of Lake George lies a hidden fleet—real shipwrecks, not stories. Dozens of vessels, some dating back more than 250 years, rest in the lake’s cold, clear depths. Preserved by the cold depths and protected from time, their wooden hulls, iron fittings, and lost cargo remain almost eerily intact. From sunken warships of the French and Indian War to forgotten steamers and scuttled barges, Lake George holds one of the most remarkable underwater archaeological preserves in North America. And they’re still down there, silent and still—witnesses to centuries of history beneath the “Queen of American Lakes.”

Beneath the famous waters of Lake George in the Adirondacks lies a world few ever see.

On the surface, the lake is all serenity—clear, still, broken only by paddleboards, tour boats, and fishing lines. Summers here are extremely busy, drawing crowds eager to escape the heat. To the casual visitor, it’s a place of recreation and postcard views. But below, a different story waits. In the cold, dark depths lie the remains of dozens of vessels—canoes, colonial warships, steamboats, pleasure craft—each with a history now sealed in silt and the silence in the depths .

Some were lost in combat. Others were deliberately sunk to keep them from enemy hands or scuttled when they outlived their usefulness. Fire, sabotage, and chance played their parts. Over time, these wrecks settled into the lakebed, protected by cold water that has preserved them with eerie clarity.

Strategic Waters: Commerce and Conflict

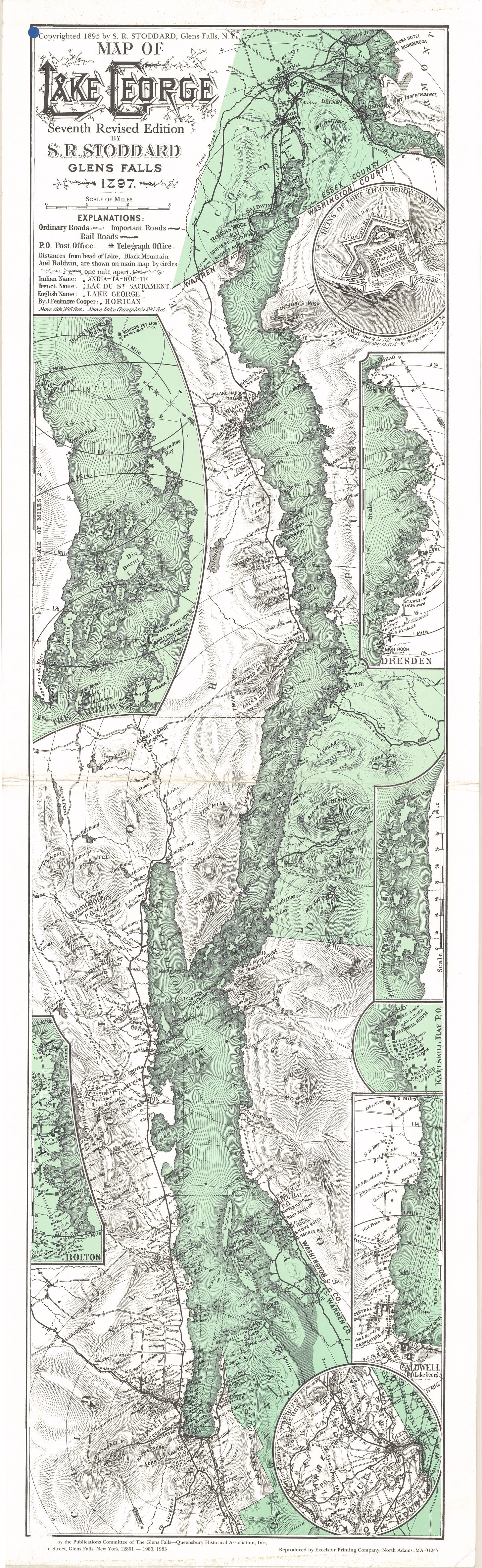

Lake George has long held strategic value—militarily, economically, and culturally. Stretching over 32 miles between the Hudson and Champlain valleys, it forms a natural corridor between New York and Canada. For Indigenous peoples, it served as a vital transportation route and spiritual landscape. For European powers, it became a highway of war.

In the 18th century, whoever controlled Lake George controlled movement through the region. It was a key segment of the inland waterway linking New York City to Montreal. British and French forces recognized this immediately. The British fortified the southern end with Fort William Henry; the French, the north, with Fort Carillon. Armies marched along the shoreline, and fleets of bateaux carried soldiers, supplies, and cannons across its waters. During peacetime, the same routes transported furs, lumber, and trade goods. The lake was as valuable to merchants as it was to generals.

1758: The Scuttled Armada

The Mohawk and Mahican called it Andiatarocte—often translated as "the place where the lake shuts itself in." To them, this stretch of water was sacred and essential, a thoroughfare that connected villages, hunting grounds, and seasonal camps. It was a place of sustenance, ceremony, and travel long before European powers ever set their eyes upon it.

Before the steamboats and cannonballs, before tourists and tour guides, the Mohawk and Mahican canoed these waters. Lake George—then known as Lac du Saint-Sacrement—was a strategic highway connecting northern and southern outposts. The lake’s geographical location provided both military and economic advantages, facilitating troop movements, supply lines, and trade routes between colonial territories.

In 1758, at the height of the French and Indian War, British General James Abercrombie assembled an immense armada at the lake’s southern end. His goal was the formidable Fort Carillon, held by the French and located strategically between Lake George and Lake Champlain. Abercrombie’s fleet comprised hundreds of vessels: sturdy bateaux, sleek sloops, and a uniquely designed warship named the Land Tortoise—a seven-sided floating battery constructed to support infantry attacks from the lake. It was armed heavily with cannons intended to breach French defenses.

However, Abercrombie’s assault on Fort Carillon ended disastrously. Facing unexpected resistance and heavy losses, the British forces retreated, leaving the lake crowded with their now-vulnerable vessels. With winter approaching, the decision was made to prevent enemy seizure by sinking their own fleet—an estimated 260 vessels deliberately submerged into Lake George’s frigid waters. This tactical destruction was meant to be temporary, with the intent to raise and reuse the fleet in the spring. Many were recovered; some were not.

The Land Tortoise vanished completely into more than 100 feet of dark water at coordinates 43.421111°N, 73.708333°W, preserving it remarkably for two centuries. Rediscovered by divers in 1990, this floating fortress emerged from history—its hull intact, its cannons still poised—appearing eerily as it had on that autumn day in 1758. Today, it stands as the oldest intact warship in North America—a remarkable relic from a time when war was waged on lakes. Its resting place is now a carefully protected underwater preserve: a wooden ghost suspended in silence.

Smoke and Steam: The Steamboat Century

The first commercially successful steamboat service in America was launched by Robert Fulton in 1807, but it would be another decade before steam arrived on Lake George. That milestone came in 1817 with the launch of the James Caldwell, a peculiar craft built in the style of a canal boat, powered by salvaged, third-hand engines and sporting a brick smokestack. Despite making the journey up the lake in roughly a day—about the same time it took to row—the James Caldwell struggled to gain traction. She mysteriously burned at her dock just four years later, in 1821, with rumors of over-insurance swirling.

Though Lake George’s shore communities were skeptical of steam technology, the success of steamboats on nearby Lake Champlain proved persuasive. On April 15, 1817, the New York State Legislature incorporated the Lake George Steamboat Company. It would become one of the longest-operating transportation companies in American history.

In 1824, the Mountaineer replaced the ill-fated James Caldwell. Built at Pine Point, she was innovative—using layered oak planks instead of a ribbed frame, an early experiment in what we now call plywood. The Mountaineer made two weekly trips to Ticonderoga and was known for its quirky boarding policy: women were welcomed with a stop; men had to row out and hop aboard from a trailing rowboat while the steamer remained in motion.

By the 1830s and 1840s, steam travel was established on the lake. The William Caldwell (1838) boasted a powerful “steeple-engine” and could travel at speeds of 12 mph, while the John Jay (1850) reached 13 mph with a 75-horsepower engine. Tragically, the John Jay caught fire during a storm on July 29, 1856, and sank after striking rocks near Cook’s Island. Six lives were lost, marking the worst marine disaster on Lake George until the Ethan Allen capsized in 2005. The wreck was later moved in an effort to salvage its engines for reuse on future vessels.

The first Minne-Ha-Ha was launched in 1857 using the salvaged engine and boiler from the John Jay. She marked a turning point in design, appearing more like the classic steamboats we picture today. With two decks and a capacity of 400 passengers, she burned six cords of wood per round trip—the last steamer on the lake to do so. She was later converted into a floating hotel annex before succumbing to ice damage and sinking near Black Mountain Bay.

The 1870s brought new innovations and expansions. The side-wheeler Horicon (1877) reached 20 mph and became a symbol of grandeur, ferrying thousands during the lake’s golden era. A young Theodore Roosevelt and Civil War General George McClellan were among her notable passengers. She was retired in 1911 and dismantled, but not forgotten.

Her successor, the steel-hulled Horicon II, launched in 1910, was the largest and fastest steamboat to ever sail Lake George—230 feet long and capable of carrying 1,500 passengers at 21 mph. She operated until 1939, surviving the Great Depression and briefly serving as a floating dance hall with big bands onboard.

Other vessels, like the Ticonderoga I, were also lost to fire. The Ticonderoga I burned in 1901 after an early morning fire erupted during a routine boiler warm-up. Despite efforts to extinguish the flames, she drifted and sank in Heart Bay.

Today, the steamboat tradition is carried forward by the Mohican II, launched in 1908 and still in active service, and the modern Minne Ha Ha II, an authentic sternwheeler launched in 1969. The Lac du Saint Sacrement, the largest boat on the lake today, was launched in 1989 and continues the tradition of elegance, offering fine dining and charters.

From the earliest wood-fired paddleboats to the diesel-driven vessels of today, Lake George's steamboat century was forged in smoke, steam, and steel. Each vessel—whether resting in silt or still slicing through water—tells the story of a lake shaped as much by human ambition as by natural beauty.

Among these disasters were stories of sabotage, negligence, and misfortune. The steam yacht Helen II, for example, was deliberately scuttled in 1933 after its owners faced financial ruin. Its wreck lies quietly beneath the waves, one among many historical secrets resting silently on the lakebed.

Timber-hauling barges from the World War I era—long, low vessels used in the region’s thriving logging industry—were deliberately scuttled when their service ended. Their skeletal frames remain in the lake’s northern basin, drawing curious divers and researchers.

Another mysterious chapter lies with the R.H. McDonald, a private steamboat later used for commercial work, reportedly lost under suspicious circumstances near Diamond Point in the early 20th century. Its story has become more folklore than fact, but rumors of its location continue to swirl among local historians.

And then there’s the Lake George Barge—a massive utility vessel, often confused with passenger wrecks, now largely forgotten save for its outline on sonar scans in the southern basin.

2005: The Ethan Allen

Even in the 21st century, the lake still claims what it wants. On a calm October 2nd in 2005, the 40-foot tour boat Ethan Allen embarked from Lake George Village, carrying a group of senior tourists from Michigan and Ohio. The day was sunny and clear, perfect for sightseeing. However, tragedy struck swiftly as the vessel abruptly capsized near Cramer Point, just minutes into the cruise. Twenty passengers lost their lives, while the remaining survivors clung desperately to the overturned hull or treaded water until rescuers arrived.

Investigations revealed that the boat had been legally operating but was overloaded due to outdated passenger capacity guidelines. Originally certified for more passengers based on a lower average weight calculation, it proved unstable when fully occupied. The rapid capsizing left a lasting mark on the community and led to major reforms in maritime safety regulations. The site is located at coordinates 43.456953°N, 73.689938°W, just offshore from Cramer Point. The craft was removed as part of the investigation.

That tragedy—starkly modern yet hauntingly familiar—echoed the lake’s history of loss and the indifferent power of water. Even today, the waters of Lake George remain impartial, holding memories quietly beneath their serene surface.

Beneath the still surface of the lake lies a hidden archive. Ships once loaded with purpose now rest in silence, their wooden hulls and iron bolts slowly surrendering to time. But this isn’t ruin—it’s remembrance. These wrecks are artifacts, each one a chapter in the story of how we lived, built, and traveled. The lake doesn’t forget. And neither should we.

Notable Wrecks of Lake George

Land Tortoise (1758)

A colonial floating battery scuttled by British forces during the French and Indian War. One of the oldest known wrecks on the lake.

Location: 43.421111°N, 73.708333°WJohn Jay (1856)

A sidewheel steamboat lost to fire during a storm on July 29, 1856. Six lives were lost—the lake’s worst maritime disaster until 2005. The wreck was later hauled to shallower water to salvage its machinery.

Location: Approx. 43.744633°N, 73.498650°W (relocated)Ticonderoga I (1901)

This elegant wooden steamer caught fire near Roger’s Rock after an early boiler firing. She drifted ablaze and ultimately sank in Heart Bay.

Location: Estimated near Heart Bay; exact coordinates unknownMinne Ha Ha I (1857)

The lake’s last wood-burning sidewheeler. After retirement, she served as a floating hotel annex before succumbing to ice damage and sinking in Black Mountain Bay.

Location: Near Black Mountain Bay, roughly 14 miles north of Lake George VillageHelen II (1933)

A private steam yacht reportedly scuttled following its owner’s financial collapse. Long rumored to rest beneath the waves, its location is intentionally undisclosed.

Location: Withheld to protect the siteEthan Allen (2005)

A modern tour boat that tragically capsized during a sightseeing cruise, resulting in 20 fatalities.

Location: 43.456953°N, 73.689938°WWWI-era Logging Barges

Timber-hauling scows used during the early 20th century, many of which were later scuttled in the lake’s northern basin.

Location: Varies; general vicinity of northern Lake George

Not Wrecks, but Often Misreported

Sagamore (1902–1937)

Often mistaken as a wreck, the Sagamore was actually dismantled on land at Baldwin. No known underwater remains exist.Horicon I (1877–1911)

Though she once reigned as the queen of the lake, the Horicon was dismantled after retirement. Like her sister ships, she never became a wreck.Mohican I (1894–1908)

Retired and taken apart in Ticonderoga upon replacement by the steel-hulled Mohican II.Ticonderoga III (2003– )

A working barge still in active use for maintenance, fireworks, and transport. Sometimes mistaken for a sunken vessel, but very much afloat and functional.

Additional Resources

Zarzynski, Joseph W., and Lyon, Bob. Lake George Shipwrecks and Sunken History

Bateaux Below, Inc. — Nonprofit organization documenting submerged heritage

New York State Museum & NYS Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation (OPRHP)

Adirondack Explorer archives and oral histories

National Register of Historic Places — Submerged Heritage Preserves

Map, 1897, Seneca Ray Stoddard, https://digitalworks.union.edu/arl_maps/25/

Lake George Steamboat Company and Luther Dow,

What is Restoration Obscura?

The name Restoration Obscura is rooted in the early language of photography. The camera obscura—Latin for “dark chamber”—was a precursor to the modern camera, a box that transformed light into shadow and shadow into fleeting image. This project reverses that process. Instead of letting history fade, Restoration Obscura brings what’s been lost in the shadows back into focus.

But this is more than photography. This is memory work.

Restoration Obscura blends archival research, image restoration, investigative storytelling, and historical interpretation to uncover stories that have slipped through the cracks—moments half-remembered or deliberately forgotten. Whether it's an unsolved mystery, a crumbling ruin, or a water-stained photograph, each piece is part of a larger tapestry: the fragments we use to reconstruct the truth.

History isn’t a static timeline—it’s a living narrative shaped by what we choose to remember. Restoration Obscura aims to make history tactile and real, reframing the past in a way that resonates with the present. Because every photo, every ruin, every document from the past has a story. It just needs the light to be seen again.

If you enjoy stories like these, subscribe to Restoration Obscura on Substack to receive new investigations straight to your inbox. Visit www.restorationobscura.com to learn more.

You can also explore the full archive of my work at www.johnbulmermedia.com.

Every Photo Has a Story.

© 2025 John Bulmer Media & Restoration Obscura. All rights reserved.

Content is for educational purposes only.

Thank you for the peace. I spent a lot of time as a kid around Lake George.

In searching on Google Earth, the 3 GPS coordinates listed, only one (Ethan Allen) seems to be correct. Land Tortoise appears to be just a few yards of the northeast corner of Lake George Steamboat dock. The John Jay coordinates are on land near the Hague town beach. Am I using the correct mapping program?