A new full-length episode of the Restoration Obscura Field Guide podcast drops Monday, May 19th, on all major streaming platforms.

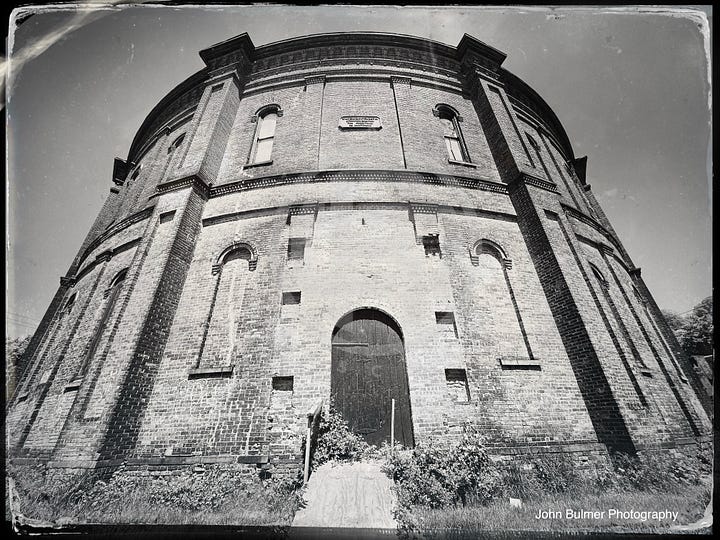

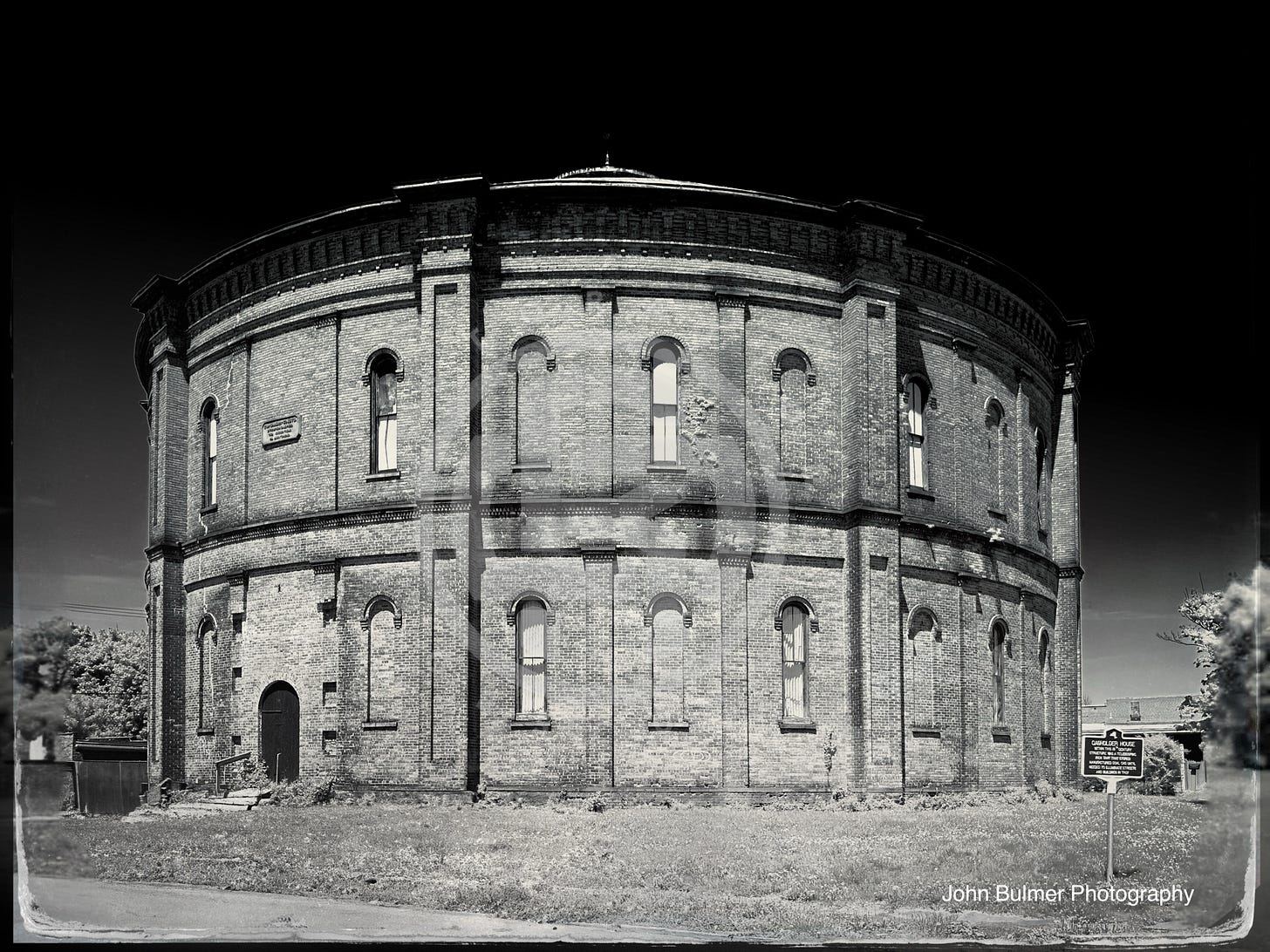

If you live in the Capital District and have ever driven through South Troy, chances are you’ve seen it—that massive round brick structure rising like a drum just off Jefferson Street. Maybe you passed by without giving it much thought. Or maybe it caught your eye, stirred something, made you wonder. That’s the Troy Gasholder House, one of the last of its kind in the country.

Today it stands quiet and empty, but its presence is impossible to ignore. Built in 1873, the Gasholder House is a relic of the gaslight era, when cities were lit not by electricity but by flame fed through underground pipes. The building once enclosed a massive iron tank that rose and fell with the city’s need for light, like a lung. Inside, the space feels almost sacred, open, circular, echoing. Being there is like stepping into a forgotten cathedral built for something no longer understood.

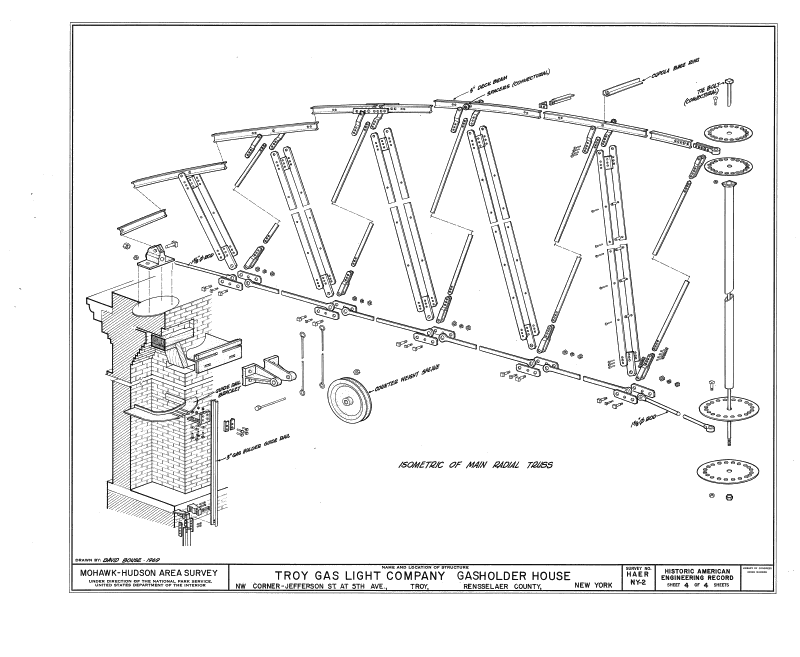

It was designed by Frederick A. Sabbaton, one of the leading gas engineers of the 19th century. The Gasholder wasn’t just practical—it was precise. At its core was a two-lift telescoping tank that could store more than 333,000 cubic feet of manufactured gas, all housed within a 109-foot-wide drum of red brick. It’s a surviving piece of a vanished network, a structure built for a purpose that no longer exists—yet it remains, intact and imposing, a rare artifact to the age of gaslight.

The process began just a few blocks north, where coal was loaded into airless iron ovens known as retorts, long, horizontal chambers built to withstand intense heat. In these sealed environments, the coal was roasted without oxygen, breaking down into volatile gases. These gases, thick with energy and impurities, were siphoned off, then cooled, scrubbed, and purified before being pumped through underground mains to this colossus. As night fell, the city’s need for light surged, and the gasholder responded. Its iron lifts would rise silently within the building like a steel chrysalis, powered by gas pressure and buoyed by a subterranean tank of water that sealed the gas inside. When demand dropped, the lifts descended with equal grace, regulating pressure and storing surplus energy for the next wave of darkness.

This structure breathed in rhythm with the life of Troy. Streetlamps, factory floors, parlors, and storefronts—all drew their glow from this cylindrical heart. It was a living mechanism embedded within the urban fabric, making it possible for Troy to shine long after the sun had set.

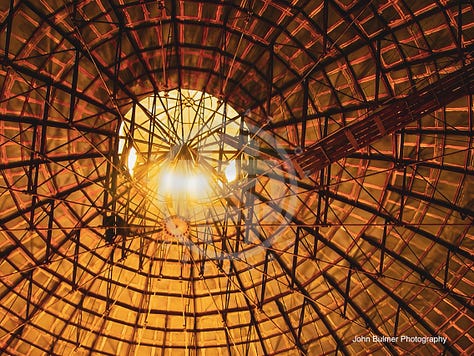

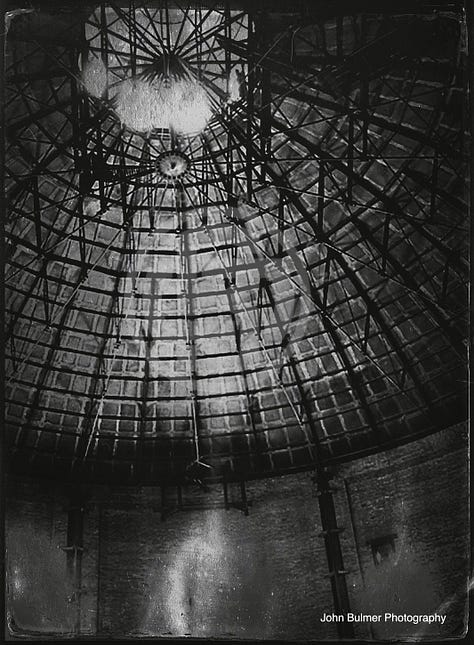

Today, the tank is long gone, dismantled for scrap in the 1930s, but the building remains. Photographing the interior structure is fascinating, especially when you begin to consider the technological innovation required to construct such an intricate system in the 1870s. This wasn’t my first time in a forgotten space—years of urban exploration have taken me through factories, sanatoriums, and silent tunnels. But the Gasholder isn’t a ruin in the traditional sense. It’s intact.

Standing inside it is like being in a giant chamber with a dirt floor and vaulted iron ceiling, an in-between place that feels both indoors and outdoors at once. Light streams through narrow slits and filters down in beams, illuminating motes of dust and painting the brick walls in amber. Sound behaves strangely here: it echoes, swirls, then vanishes. The silence feels designed.

Photographing places like this matters. It’s not just about documenting what’s there—it’s about trying to understand it. Historical photography helps us do more than preserve the past; it helps us make sense of it. A good image can bring something forgotten back into focus, even just for a moment. It lets others see what’s usually hidden, especially those who might never get the chance to step inside.

The gasholder was a technological solution to a very human need: the desire to conquer the night. Before gaslight, cities were places of deep shadow after sundown. Candles and oil lamps were fickle, dim, and dangerous. But with manufactured gas came illumination, bright, consistent, centralized. The first gaslit streets in America appeared in Baltimore in 1816. By the 1840s, gas had become the backbone of urban light. Troy adopted it in 1848, establishing the Troy Gas Light Company, which would hold a monopoly on gas production for nearly three decades.

But gas didn’t just illuminate the city, it shaped it. Factories extended their hours. Streets grew safer. Shops stayed open later. And new infrastructure was built, including underground mains, retort houses, and of course, the gasholder itself. This storage facility, crucial for balancing production with unpredictable consumer demand, allowed the entire system to function efficiently. It acted as a buffer, regulating pressure and storing gas during off-peak hours. Without it, the city’s lighting would have faltered, leaving homes and streets in the dark.

The design of the gasholder was as practical as it was grand. The tank’s two iron lifts nested inside one another, rising and falling based on gas volume. A water seal at the base kept the gas contained. The brick house surrounding it served both functional and symbolic roles. It protected the tank from weather, insulated the water seal against freezing, and quelled public fears about explosions. But more than that, it was a civic landmark. Its corbelled cornices, arched windows, and domed roof made it an unmistakable feature of Troy’s skyline—a beacon of modernity in a rapidly industrializing city.

Troy itself was booming. Known as the "Collar City" for its detachable shirt collar industry, it was also a major player in ironworks, textiles, and machine manufacturing. By the 1840s, it was among the wealthiest cities per capita in the United States. The gasholder house symbolized this prosperity, tying together the city's economic ambition with its infrastructural foresight. It was not a leftover curiosity—it was central to how Troy functioned and grew.

The eventual decline of the gaslight era was slow but inevitable. Electric lighting emerged in the late 19th century, offering cleaner and increasingly more efficient illumination. The incandescent gas mantle and other gas innovations extended the life of the industry, but the writing was on the wall. In the 1920s, gas production shifted to a centralized plant in Menands. By the 1930s, the Troy Gasholder's iron tank was scrapped, and the building repurposed.

Since then, the gasholder has had a second, quieter life. It has served as a storage facility, a garage, and an unlikely performance space. Bands have practiced inside its acoustically curious walls. Dancers and artists have filled it with movement and sound. Each use layers new meaning onto the structure, even as its original function fades further into memory.

Today, it stands preserved, listed on the National Register of Historic Places and recognized as an engineering landmark by the Historic American Engineering Record. Its profile even serves as the logo for the Society for Industrial Archaeology. These honors are well-earned. There are only a dozen or so such gasholder houses still standing in the U.S., and Troy's is arguably the most impressive.

But preservation isn’t just about plaques and historic status, it’s about paying attention. It’s about standing in that vast brick drum and imagining the hiss of gas lines, the roar of the furnaces, the slow rise of the iron tank. It’s about photographing what remains not just to show what it looked like, but to convey what it felt like.

Capturing places like the Troy Gasholder helps us remember a time when cities were lit by flame and powered by coal. These spaces connect us to the way people once lived, worked, and moved through the world. And in recording them, we hold on to something that might otherwise disappear.

About Restoration Obscura

Restoration Obscura is where overlooked history gets another shot at being seen, heard, and understood. Through long-form storytelling, archival research, and photographic restoration, we recover the forgotten chapters—the ones buried in basements, fading in family albums, or sealed behind locked doors.

The name nods to the camera obscura, an early photographic device that captured light in a darkened chamber. Restoration Obscura flips that idea, pulling stories out of darkness and casting light on what history left behind.

This project uncovers what textbooks miss: Cold War secrets, vanished neighborhoods, wartime experiments, strange ruins, lost towns, and the people tied to them. Each episode, article, or image rebuilds a fractured past and brings it back into focus, one story at a time.

If you believe memory is worth preserving, if you’ve ever felt something standing at the edge of a ruin or holding an old photograph, this space is for you.

Subscribe to support independent, reader-funded storytelling: www.restorationobscura.com

🎧 The Restoration Obscura Field Guide Podcast is streaming now on all major streaming platforms.

Every photo has a story. And every story connects us.

© 2025 John Bulmer Media & Restoration Obscura. All rights reserved. Educational use only.

Permissions Statement

Restoration Obscura may not hold copyright for all images featured in its archives or publications. For uses beyond educational or non-commercial purposes, please contact the institution or original source that provided the image.

I have actually been inside that place! Fascinating how nearly forgotten history is all around us, if we but look. I love your series, by the way. Keep it going.

What were the accoustics like? I wonder if it could be repurposed as a venue.