Before trucks and railroads, the rivers of the Adirondacks were the only roads that could carry the weight of the timber trade. Each spring for more than a century, snowmelt turned mountain streams and the Hudson River into wild, dangerous passageways for logs. It wasn’t just a job—it was a way of life, shaped by long days, hard labor, and the close-knit crews who lived it together.

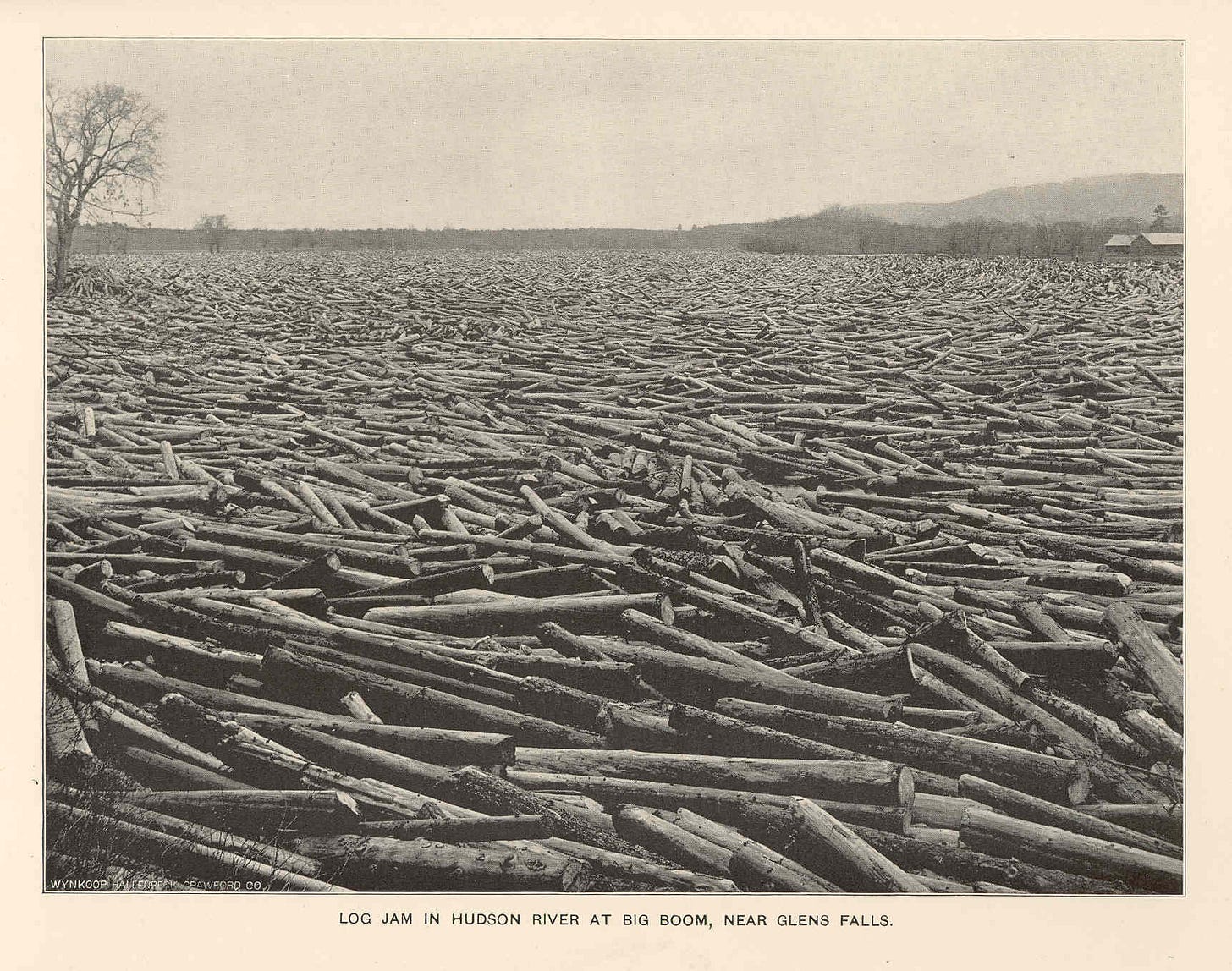

From the remote logging camps deep in the forest to the massive log-sorting structure known as the Big Boom in Glens Falls, the story of the log drives is one of grit, invention, and deep environmental change. These rivers didn’t just move wood—they moved an entire region forward, carving a path into the industrial age with every passing log.

Through the lens of photographers like Seneca Ray Stoddard, the world caught a glimpse of what it cost. His glass plates captured both the men who ran the rivers and the marks their work left behind.

From Forest to Mill

The lumber trade in the Adirondacks began to take off in the early 1800s, drawn by vast stands of white pine and red spruce—tall, straight trees that were perfect for building materials and export. Early sawmills popped up along fast-moving streams, using the current to power their saws. But it was the idea of floating raw logs downriver that really allowed the industry to grow.

By the 1820s, Glens Falls had become the heart of the trade. The town sat just below a natural waterfall on the Hudson River, which provided both power for the mills and a natural place to catch and collect the incoming logs. As more companies sent timber down the river each spring, the system became overwhelmed. Logs jammed. Tempers flared. Some companies even tried to steal logs by cutting off the identifying marks and claiming them as their own.

In 1849, local mill owners came together to form the Hudson River Boom Association. Their solution was the Big Boom—a massive wooden barrier stretched across the river above Glens Falls. It guided millions of floating logs into sorting pens based on the brand each company stamped into the wood. It brought some order to the chaos, though the work remained anything but safe.

The River Pigs

The lifeblood of the log drive wasn’t machinery—it was men. Known as river drivers, or more colorfully as “river pigs,” they were tough, skilled laborers who moved with the water, guiding logs through narrow channels, breaking up snarled jams, and sometimes riding a single log like a surfboard through the spray.

Armed with peaveys and pike poles, they danced across slick, rolling timber with uncanny balance. Their tools became part of them—extensions of muscle and instinct—used to jab, pry, and twist tangled logs free. At places like Ord Falls near Newcomb or the Deer Den below the Blue Ledges, where the river turned violent, their work was part acrobatics, part survival. Many didn’t make it. Some were crushed beneath collapsing jams. Others slipped into the freezing current and never came out.

The most agile could ride a single log across flatwater stretches like Blackwell Stillwater, using their poles like tightrope walkers’ staffs. Others fashioned rough rafts—called “cooters”—by tying two or three logs together, choosing the river over snow-choked, rocky shorelines.

At day’s end, they gathered in long lean-tos along the riverbank, some stretching forty feet, with open fires burning across the front to dry soaked clothes and thaw chilled hands. Cast iron pots of beans and ham hung over the flames. Nights were cold. Mornings colder. Years of wet boots and strain left many men with twisted joints and rheumatism before they ever reached old age.

Timing the Waters

The log drives began like clockwork each spring, just after the snowmelt. In places like Cedar Lakes, dams were opened to build up a surge of current downstream. Once enough water had gathered, the boom was cut loose, and the logs began their long descent. From Cedar Lakes to the Hudson, the wood traveled more than a hundred miles, reaching the Big Boom in Glens Falls within two or three days if the current was strong.

Spring rains and freshets were essential. Too little water, and logs would beach themselves on the banks or splinter on hidden rocks. Too much, and the river could surge out of control—washing out bridges, tearing through banks, and pulling both logs and men into the depths.

Each log carried a brand—usually a number—burned or stamped into the end to mark ownership. One of the earliest loggers on the upper Hudson, Jones Ordway, used the number "34" for Township 34, around Blue Mountain Lake. When he died in 1890, Ordway left behind a fortune of half a million dollars and a towering 40-foot marble monument in Glens Falls—an echo of the forests that made him.

The logs themselves were measured using a unit called a “market”—a term unique to the upper Hudson. A single market referred to a log 13 feet, 4 inches long and 19 inches wide at the narrow end, containing about 200 board feet of lumber. Larger or smaller logs were counted as fractions or multiples of that standard. In 1872, the busiest year for the Big Boom, more than a million markets passed through Glens Falls—enough lumber to frame a city.

Stoddard’s Legacy

Photographers like Seneca Ray Stoddard were more than documentarians—they were some of the earliest voices to sound the alarm about the environmental cost of industrial expansion. Stoddard wasn’t content to simply capture men working the rivers; his lens turned just as often toward the aftermath—the stripped hillsides, the scarred shorelines, and the drowned lands left behind. He understood that photography had power—not just to record, but to persuade.

In his 1891 Illustrated Guide to the Adirondacks, Stoddard issued a stark warning: if the uplands weren’t preserved, the state’s rivers would become nothing more than “sluice-ways for carrying off the spring freshets.” He had seen it happen already. Logging had intensified at such a pace that the forests couldn’t recover. Virgin white pine forests, centuries in the making, were clear-cut in a matter of weeks. Hemlocks were felled not for timber but for their bark, used in the tanning industry—leaving behind entire forests of rotting trunks, abandoned as waste.

To move timber more efficiently, loggers often dynamited streams and riverbeds to clear obstacles, blasting away natural barriers that had shaped ecosystems for millennia. Riverbanks were chewed away by the relentless passage of millions of logs. Sediment clouded the water, smothering fish spawning beds and wiping out native trout populations. Shade trees that once cooled the streams were gone, raising water temperatures and altering aquatic life. Wetlands, vital for absorbing runoff and supporting biodiversity, were drained or submerged behind temporary dams used to build up spring surges.

Stoddard documented all of this—not with dramatic flourishes, but with quiet, relentless clarity. His photographs were presented to lawmakers in Albany alongside his words. He argued that unregulated logging in the Adirondacks would not only destroy natural beauty but also threaten the water supply of New York State, which depended on the Hudson River and its tributaries. At the time, New York City and other growing population centers relied heavily on mountain-fed watersheds. If the forests were lost, so too would be the natural filtration and steady flow of water those forests provided.

He wasn’t alone in his concern, but his voice was one of the most visible. The haunting image titled Drowned Lands—showing a once-forested wetland reduced to a swamp of stumps and standing water—became a visual flashpoint. It wasn’t just a photo; it was evidence. Stoddard carried it to the State Legislature as part of a push for forest protection, helping to turn public opinion in favor of what would become the Forest Preserve and the “Forever Wild” clause of the New York State Constitution, adopted in 1894.

In a time when conservation was barely a word, Stoddard’s work made a case that preservation was not just about saving scenery—it was about protecting the very systems that sustained life. His lens saw farther than most, capturing not only what was happening in the moment, but what might happen if the land wasn’t given a chance to heal.

The End of the Drive

The golden era of the log drive didn’t last. What had once been a seasonal ritual—a thunderous, coordinated movement of men and timber down the arteries of the Adirondacks—began to fade in the early 20th century. The reasons were practical: railroads and trucks could move timber faster, more safely, and with less dependence on weather and water levels. Log drives were dangerous, unpredictable, and increasingly out of step with modern transportation methods.

As road networks improved and internal combustion engines became more reliable, trucks began hauling sawlogs and pulpwood year-round, bypassing the rivers entirely. Rail lines reached deeper into the woods, connecting logging camps directly to processing mills. What had once required a dangerous spring journey by river could now be done by locomotive in a matter of hours.

Sawmill towns like Glens Falls, which had thrived on the river’s seasonal bounty, began to adapt. Companies like Finch Pruyn, a dominant force in the region’s timber economy, shifted operations accordingly. While the company ended its sawmill operations in the 1920s, it continued to use the river to float pulpwood—logs destined for paper production—until 1950. That final spring, as one last log drive made its way down the upper Hudson, the era quietly came to a close.

The Big Boom, once a marvel of engineering and a symbol of Glens Falls’ industrial might, ceased operation two years later in 1952. For over a century, it had sorted millions of logs, each marked with the stamp of its owner, into pens that fed the town’s hungry saws. When the last boom logs were cleared, it marked not just the end of a method—but the passing of a culture.

With it went the river drivers, the lean-to camps, the red bandanas, the scent of woodsmoke and wet bark. Their songs, stories, and injuries faded into memory. The river ran quieter now. The scars on the banks began to soften, though the marks of the trade—rusted iron rings, embedded cables, and battered stone abutments—still remain in places if you know where to look.

Yet the impact of the log drives remains imprinted on the landscape and the towns they helped build. Glens Falls, once a log town, became a paper town, and later a regional hub of commerce. The forest, long overworked, began to recover under new protections. And the rivers, once choked with timber, resumed their slower, seasonal rhythms.

The log drive had done its work—not just in transporting timber, but in shaping a region’s identity, its economy, and its memory. It was a hard era, but one that defined generations.

The River Remembers

Today, little remains of the great log drives but echoes. The rivers that once thundered with timber now run quiet, their banks slowly reclaiming what industry once stripped away. Rusted iron rings still cling to boulders along the shoreline. Old bolts lie buried in the roots of trees that weren’t there a hundred years ago. Scars in the rock, worn smooth by water and time, hint at the volume of wood once forced downriver, year after year.

In museums and historical collections, fragments of that era endure: peaveys worn to a polish by callused hands, boots studded with iron corks for gripping wet logs, camp cookware blackened by riverside fires. Archival prints—creased, foxed, and fading—reveal lean faces, bent shoulders, and rivers packed so tight with timber you could walk across without ever touching water.

At the Glens Falls Cemetery, Henry Crandall’s monument rises tall above the headstones. Etched into the marble is the same star-shaped brand once stamped on the ends of his logs—symbols that floated from forest to mill, carving his legacy into the current of the Hudson.

But the most haunting records are the images left behind. Stoddard’s work, in particular, endures not just as historical documentation but as the spark that helped to create the largest publicly protected area in the contiguous United States. His lens captured not only the labor and movement of the log drives, but the silences they left behind. The denuded hillsides. The drowned lands. The skeletal trunks rising from wetlands that had once been shaded, living forests.

These images ask hard questions. What was the price of progress? What did it yield—and what did it erase? They refuse nostalgia. They offer perspective.

Restoration Obscura examines these stories—not to glorify the past, but to understand it. To trace the forgotten infrastructure of human ambition written into the land. To bring old photographs, records, and ruins into focus, so that we might better grasp the forces that shaped both the wilderness and the people who worked it.

The river’s highway remains, though quieter now. Its flow is steadier, its burden gone. Yet the history hasn’t vanished. The photographs continue to speak—quiet, powerful artifacts of a time when men moved entire forests by hand and river, and when the land bore every mark of their passing.

Look closely, and traces of that history are still visible. Much of the forest here is young — many of the trees are less than 100 years old, growing back after the peak of Adirondack logging. Scattered older trees stand out against this new growth, marking a time when the region’s forests were cut and hauled to feed sawmills, paper plants, and growing cities.

You can view my ongoing project restoring the works of Seneca Ray Stoddard here: www.senecaraystoddard.com

What is Restoration Obscura?

The name Restoration Obscura is rooted in the early language of photography. The camera obscura—Latin for “dark chamber”—was a precursor to the modern camera, a box that transformed light into shadow and shadow into fleeting image. This project reverses that process. Instead of letting history fade, Restoration Obscura brings what’s been lost in the shadows back into focus.

But this is more than photography. This is memory work.

Restoration Obscura blends archival research, image restoration, investigative storytelling, and historical interpretation to uncover stories that have slipped through the cracks—moments half-remembered or deliberately forgotten. Whether it's an unsolved mystery, a crumbling ruin, or a water-stained photograph, each piece is part of a larger tapestry: the fragments we use to reconstruct the truth.

History isn’t a static timeline—it’s a living narrative shaped by what we choose to remember. Restoration Obscura aims to make history tactile and real, reframing the past in a way that resonates with the present. Because every photo, every ruin, every document from the past has a story. It just needs the light to be seen again.

If you enjoy stories like these, subscribe to Restoration Obscura on Substack to receive new investigations straight to your inbox. Visit www.restorationobscura.com to learn more.

You can also explore the full archive of my work at www.johnbulmermedia.com.

Every Photo Has a Story.

© 2025 John Bulmer Media & Restoration Obscura. All rights reserved.

Content is for educational purposes only.

Permissions Statement

Restoration Obscura does not hold copyright for any images featured in its archives or publications. For uses beyond educational or non-commercial purposes, please contact the institution or original source that provided the image.