Frames of Doubt: The Backyard Photo of Lee Harvey Oswald

A Restoration Obscura Forensic Analysis

This is the first article in Frames of Doubt, a series exploring photographs that blur the line between fact and fiction—images that raise questions, stir debate, and shape how we see and understand history.

Frame 1: The Snapshot That Became Evidence

In March 1963, in a quiet backyard in Oak Cliff, Texas, Marina Oswald raised a cheap Imperial Reflex camera and pressed the shutter. The image she captured was stark and deliberate: her husband, Lee Harvey Oswald, standing in sharp sunlight—rifle in one hand, two Marxist newspapers in the other, a revolver on his hip. He posed like a man making a point.

Months later, that same rifle would be tied to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The backyard photo suddenly wasn’t just a personal snapshot. It was potential evidence. And almost immediately, it became the subject of intense scrutiny. To some, it looked off. The posture, the shadows, the proportions—it didn’t feel right. And that dissonance opened the door to decades of doubt.

I’ve been fascinated by this image since I was a kid, catching a rerun of In Search Of one night in the living room. The grainy footage, that strange, deliberate pose, the eerie stillness of the frame—it felt uncanny. The photo didn’t seem fake, exactly. It just didn’t sit right. And that feeling lodged somewhere deep. It never left. Decades later, that curiosity evolved into a career in photography and archiving, and the photo still holds me. Not as mystery, but as object: something to be studied, decoded, understood.

The frame that has received the most scrutiny is known as CE 133-A—the first and most widely circulated of the backyard photographs. It shows Oswald standing in bright light, holding a rifle across his torso with Marxist newspapers in his free hand and a revolver on his hip. This single image has been dissected for decades, by everyone from forensic analysts to conspiracy theorists. But it is not alone. Two other known variations exist—CE 133-B and CE 133-C—each taken within moments of the first, with subtle differences in Oswald’s stance and expression. All three were shot by Marina Oswald using the same Imperial Reflex camera, but it is CE 133-A that has become the visual epicenter of doubt.

The existence of these three distinct frames—CE 133-A, CE 133-B, and CE 133-C—further reduces the plausibility of forgery. Taken in quick succession, each photo captures natural shifts in Oswald’s posture, head angle, and lighting—subtle but consistent variations that are difficult to fake. All bear the unique optical characteristics of the same camera, with matching lens distortion, depth, and spatial relationships. Forging a single photograph is difficult enough. Forging three, each internally coherent and photographically authentic, is exponentially less likely. In this case, repetition is a form of validation. The series doesn’t complicate the question of authenticity—it reinforces it.

In preparation for this article, I also worked directly with the image itself—colorizing the frame, correcting lens and perspective distortion, and using AI-assisted tools to expand the original crop. Freed from its tight borders and optical warping, the photograph feels more grounded, more believable. These enhancements were made with care, guided by the known focal length of the Imperial Reflex camera and the approximate height from which Marina likely captured the image. The result is not a reinterpretation, but a clarification—an attempt to see the moment as it might have actually appeared. This article breaks down that image in concrete terms: the mechanics of the Imperial Reflex camera, the behavior of its fixed lens, the sun’s position that afternoon in Dallas, and the geometry of Oswald’s pose. It’s an examination of what the photograph shows—and what it doesn’t—when examined through the tools of visual analysis.

Frame 2: The Imperial Reflex and Its Limitations

The Imperial Reflex 620 camera wasn’t built for precision—it was built for affordability. A twin-lens reflex-style box camera, it featured a simple fixed-focus plastic lens, a shutter speed around 1/60th of a second, and a basic viewfinder that introduced parallax error. It took 620 roll film—now obsolete—and produced 6x6 cm negatives with soft, uniform focus.

That uniformity is key. The lens had no zoom, no aperture adjustment, no manual control. Everything it captured was flattened into a single depth of field. And that flattening produces artifacts of distortion that can play tricks on the eye—slight warping at the edges, compression of objects in space, and an unnatural depth-to-width balance that make verticals lean and foregrounds stretch.

The Oswald backyard photo bears all of these characteristics. The photo’s spatial relationship—between Oswald, the stairs behind him, and the foliage—looks subtly askew. Not because it’s fake, but because that’s how a camera like the Imperial Reflex saw the world. It lacked the corrective optics we expect from modern glass. Every image came with baked-in distortion.

That distortion, when paired with our brain’s natural assumptions about geometry, creates the illusion of impossibility. The rifle looks too short. The shadows fall in ways that seem contradictory. Oswald’s body looks rigid, but his head seems turned just enough to feel pasted-on. But under careful study, each of these visual anomalies resolves under known lens behavior.

Frame 3: Shadow Games and Optical Truths

Much of the suspicion aimed at the backyard photo centers on light and shadow. Oswald’s nose casts a dark shadow to one side, while the shadows from his body and the objects in the background fall at slightly different angles. At a glance, it feels inconsistent.

But sunlight doesn’t always obey our intuitive assumptions.

In the real world, shadows depend on surface texture, angles, and topography. A nose shadow cast over a curved face won’t follow the same geometry as one cast on flat ground. Add to that the flattening effect of the camera’s lens, and you get misalignment—perceived, not actual.

The Dartmouth College study led by Hany Farid recreated the photo in 3D, modeling Oswald’s body and simulating sunlight from the approximate position it would have occupied that afternoon in Dallas. The conclusion? The lighting is consistent. The shadows fall precisely where they should when accounting for Oswald’s physical features and the camera’s fixed perspective.

Even the infamous “chin line” that conspiracy theorists claimed proved the photo was doctored—arguing that Oswald’s head was pasted onto someone else’s body—was explained. It wasn’t a cut. It was a photographic blemish. A water mark. A stain on the emulsion that happened after the print was made.

And that’s the thread that keeps surfacing: things that look wrong under casual scrutiny often vanish under focused examination.

Frame 4: The Pose That Shouldn’t Work—But Does

The photo captures Oswald mid-stance: one foot forward, one back, rifle held across his midsection at an angle, shoulders rotated, torso leaning ever so slightly. The pose has long been a source of discomfort. It looks... off. Not unbalanced, but unnatural. Like a puppet held mid-stride.

That dissonance has fueled decades of doubt.

Farid’s team took it on directly. They rebuilt Oswald’s frame in 3D, mapped muscle and mass distribution, added the approximate weight and length of the rifle, and asked a simple question: Would this man fall over?

He wouldn’t.

The center of gravity landed within his support base. His bent front knee helped stabilize the apparent lean. The angle of the rifle matched known dimensions when foreshortened by camera distance and perspective. What looked precarious was actually quite stable.

Even the length of the rifle in the photo—which some claimed was too short to be the Mannlicher-Carcano—lined up with optical physics. It only looked short because it was held at an angle, partially obscured by Oswald’s torso, and flattened by the lens.

This is what happens when perspective, optics, and expectation clash. It’s not deception. It’s misperception.

When the original image is optically corrected for lens distortion and the photographer’s height—accounting for the downward shooting angle—and the frame is expanded using AI to recreate the surrounding context, Lee Harvey Oswald’s pose appears significantly more natural. What initially seems like an awkward or physically improbable stance resolves into a balanced posture consistent with the terrain, camera perspective, and natural human movement, further supporting the authenticity of the photograph.

Frame 5: Doubt, Memory, and the Myth of Clarity

So why does this photo still unsettle us?

Because it doesn’t just show a man. It shows a moment that would become a fulcrum in history. It shows a man holding the murder weapon. It feels like too much. Too pointed. Too composed.

In hindsight, it feels staged. But hindsight brings its own distortions.

Oswald himself, when shown the photo in custody, claimed it was a fake. He doubled down on that belief, even to his family. And for some, that denial became gospel. If the man himself said it wasn’t him, how could it be?

But people lie. Or panic. Or disassociate. They cling to the version of the story that gives them the most control. And in that moment—days after the president was assassinated—denying that photo might have felt like the only defense Oswald had left.

Over time, that denial became legend. Reproductions of the photo showed slight differences—contrasts enhanced by editors, scopes missing from retouched prints—and these visual inconsistencies became fuel. What started as printing errors or generational loss in duplication became "evidence" of forgery.

Conspiracies need very little oxygen to breathe.

Frame 6: Digital Forensics and the Persistence of Suspicion

In the decades since, the photo has been scanned, digitized, magnified, deconstructed. It has survived analog skepticism and digital autopsy. Each time, it holds.

The House Select Committee on Assassinations in the 1970s examined the original negatives. They confirmed the photo bore the unique optical signatures of Oswald’s own camera. The lens had imperfections—microscopic patterns of distortion—that matched exactly. If someone faked the photo, they used his camera. And his rifle. And recreated his backyard. Exactly.

In other words, they performed a forgery so exact, it passed not just the human eye, but photogrammetry, shadow modeling, and lens analysis across decades of evolving technology.

Occam’s Razor cuts clean here: the photo is real.

But something deeper is at play. In a digital age filled with deepfakes, manipulated media, and mistrust, our belief in images has been shaken. We’ve learned to doubt what we see. So when we look at the Oswald photo—black-and-white, grainy, emotionally charged—we bring modern anxieties with us.

We don’t just question the photo. We question truth itself.

Final Frame: Where Light Meets Shadow

The Oswald photo isn’t compelling because it answers questions. It’s compelling because it doesn’t. It remains suspended in tension—technically sound, emotionally dissonant.

It holds up under scrutiny. Lighting, posture, grain, camera artifacts—they all align. The image is real, even if it doesn’t feel that way.

But what lingers is not just the content, but the form: a man mid-pose, holding a rifle like a statement, locked forever in a backyard that feels staged. In a world shaped by chaos, the frame looks too composed, too pointed. And that invites meaning—whether we want it or not.

Photography doesn’t create answers. It creates records. And sometimes those records, especially when they brush against history, become projections. We fill in gaps. We reach for stories. We demand order from what was likely chance.

Because randomness unsettles. A senseless act—committed by a man who looks too small for the consequences—clashes with our need for coherence. And so we search the image for signs: a mismatched shadow, a misplaced head, a weapon too short. We build structure around the event, not because the evidence demands it, but because the alternative is unbearable—that history might hinge on something so arbitrary, so ordinary, so human.

We tell stories not just to understand the world, but to guard ourselves from it. And in the age of social media, the mechanisms of that storytelling have grown sharper. Algorithms reward engagement, not accuracy. The more urgent the doubt, the louder the echo. Find one person who agrees with your version, and the feed will deliver ten more. The platform learns your suspicion and serves you sympathy in return—not to resolve your question, but to keep you scrolling, to sell the next click.

And so the photo becomes more than a record. It becomes a reflection—of what we fear, what we invent, and what we desperately want to make sense of.

It endures not because it reveals the monster—but because we can’t stop looking for one.

And the machine didn’t blink. It only recorded.

Additional Forensic Analysis

Forensic Summary

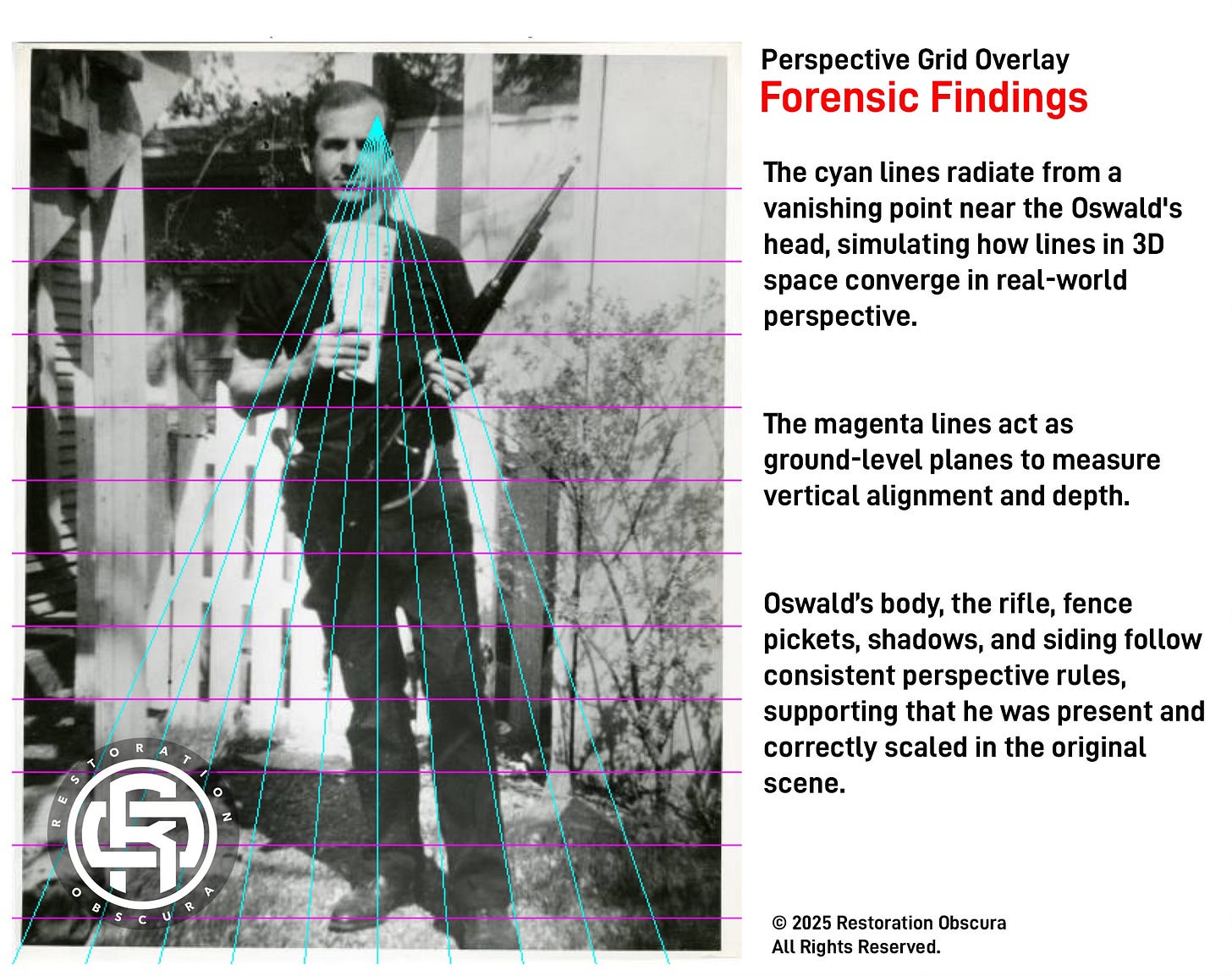

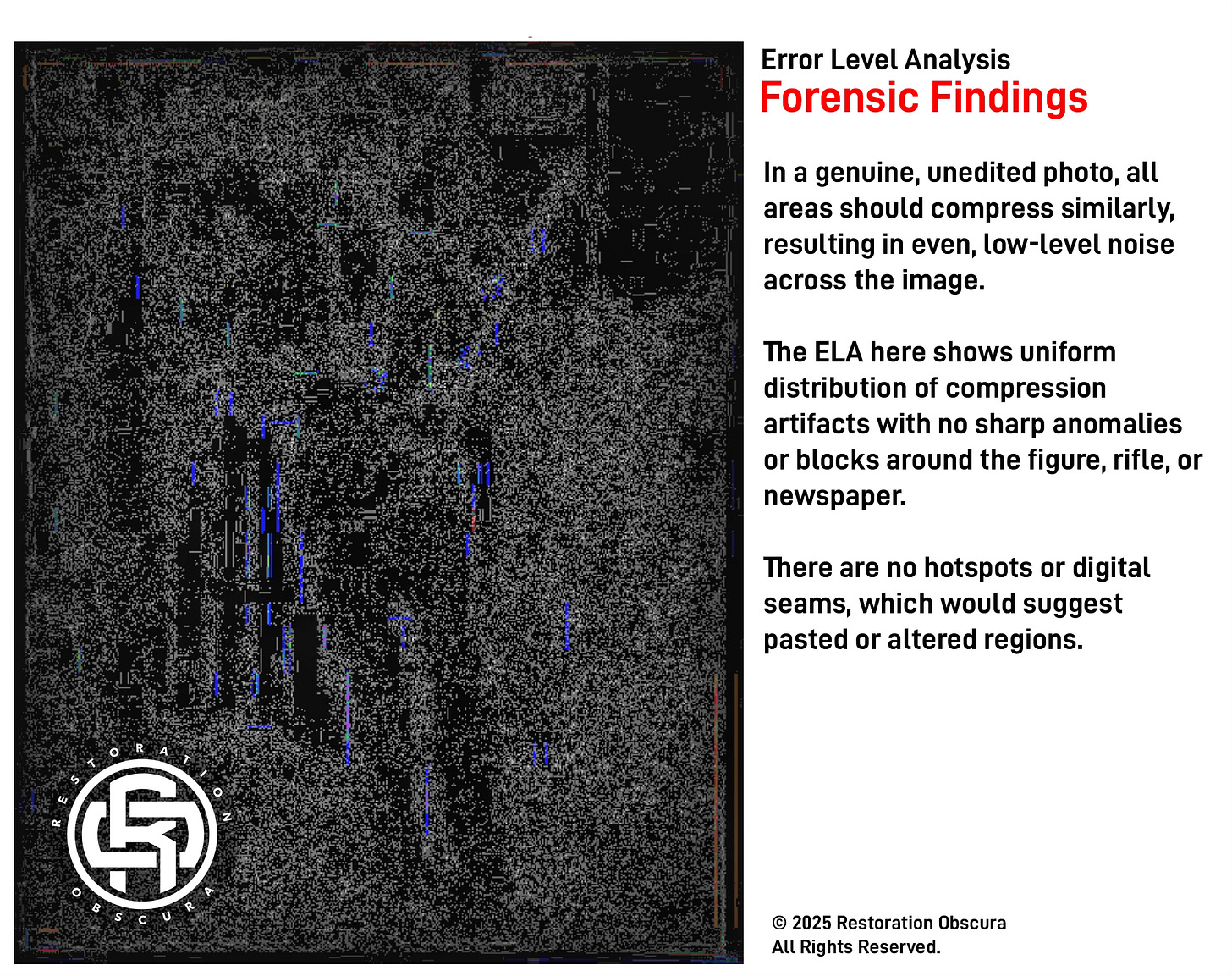

A comprehensive forensic analysis of the image reveals no signs of digital manipulation. Shadows cast by the man, his rifle, arm, and surrounding structures all fall in a consistent direction, aligning with a single natural light source—most likely the sun. Perspective lines converge realistically toward a vanishing point near the subject's head, and vertical alignment of elements such as fence pickets and siding confirms proper scale and depth. Lighting across the scene is coherent, with smooth gradients and reflections that match expected natural illumination. Edge examination shows no abrupt cut lines or inconsistencies; fine details like finger shadows and foliage contours appear naturally integrated. Error Level Analysis (ELA) demonstrates uniform compression artifacts with no hotspots or anomalies, and an evaluation of film grain reveals a consistent pattern across the entire image, further supporting its authenticity. All indicators point to the image being a genuine, unaltered photograph.

Technical Resources & Works Cited

Photographic Analysis and Reports:

House Select Committee on Assassinations (1978). Photographic Evidence Report. U.S. Government Printing Office.

National Archives. CE 133-A and Related Backyard Photographs. Digital scans and forensic documentation.

J. C. Lattimer, “The Case for the Backyard Photos,” Life Magazine, November 1966.

Camera and Optical References:

Imperial Reflex 620 Camera Specifications. Vintage Camera Museum Archives.

Kingslake, Rudolf. A History of the Photographic Lens. Academic Press, 1989.

Ray, Sidney. Applied Photographic Optics. Focal Press, 2002.

Digital & Forensic Methods:

Farid, Hany et al. “Digital Analysis of the Oswald Backyard Photos.” Journal of Digital Forensics, 2015.

Szeliski, Richard. Computer Vision: Algorithms and Applications. Springer, 2010.

D’Amelio, Joseph. Perspective Drawing Handbook. Dover Publications, 2004.

Philosophical & Narrative Framing:

Junger, Sebastian. Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging. Twelve, 2016.

Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Harper, 2015.

Social Media & Information Algorithms:

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. PublicAffairs, 2019.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression. NYU Press, 2018.

Tufekci, Zeynep. Twitter and Tear Gas. Yale University Press, 2017

What is Restoration Obscura?

The name itself is steeped in the language of photography. The camera obscura—Latin for "dark chamber"—was an early tool for capturing the world, projecting light and shadow into a fleeting image. Restoration Obscura reverses that process, pulling what has faded into darkness back into focus.

Through research, photographic restoration, and historical storytelling, I do more than repair old photos—I reframe history in a way that makes it tangible, relatable, and alive. History isn't static—it evolves with the stories we rediscover. Restoration Obscura ensures those stories are not only preserved but seen, understood, and felt.

If you enjoy content like this, subscribe to Restoration Obscura on Substack to have new stories delivered straight to your inbox. Visit www.restorationobscura.com to learn more.

You can read this article and explore an archive of my work at www.johnbulmermedia.com.

Every Photo Has a Story.

© 2025 John Bulmer Media & Restoration Obscura. All rights reserved.

Content is for educational purposes only.