Albany Underground A History of Albany’s Tunnels

Beneath the noise of the city — beneath its streets — runs a hidden network of access and utility tunnels: a shadow infrastructure few ever see, but one that quietly sustains the city above.

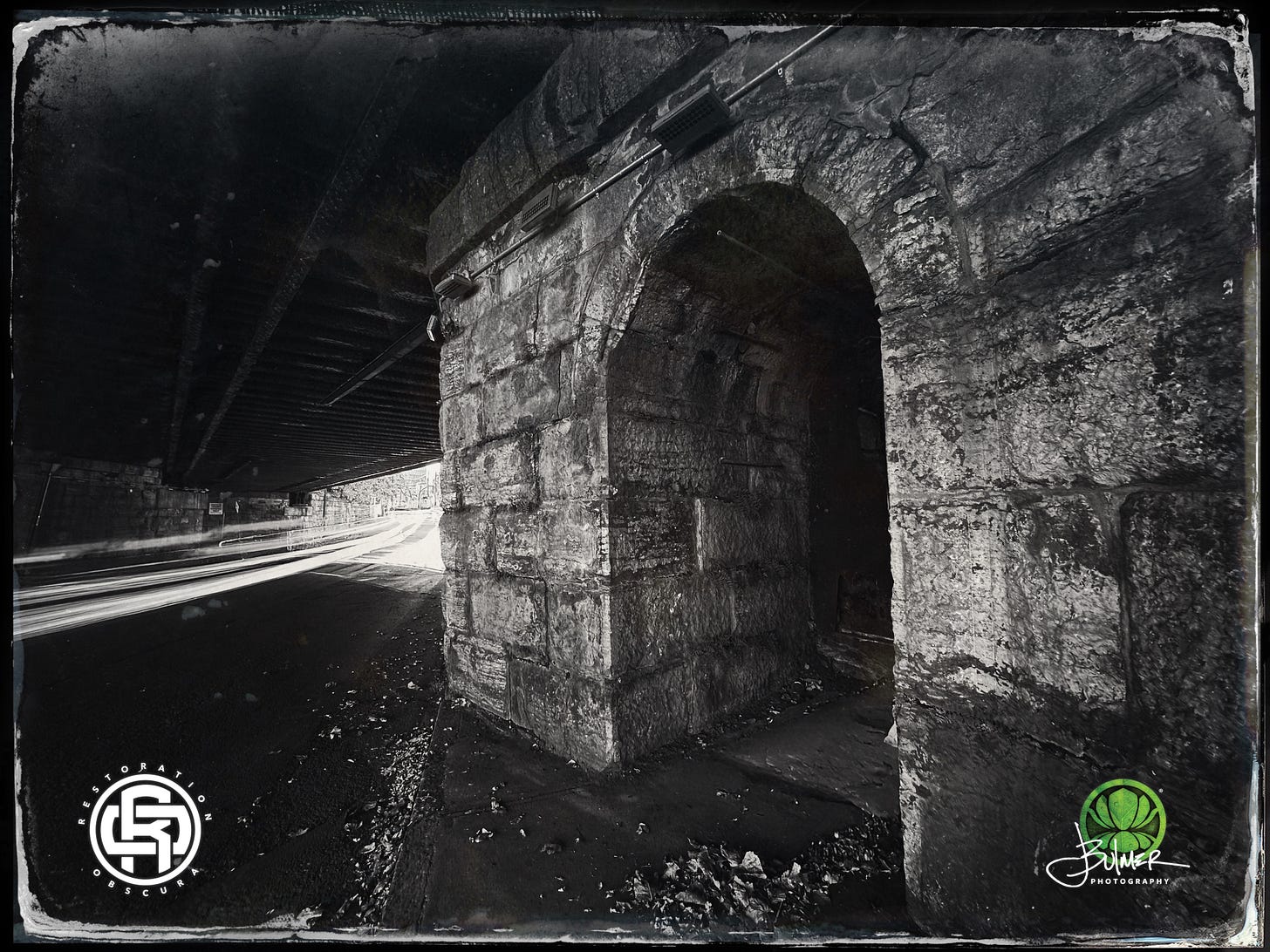

A person hurries down a crowded street — lost in the rhythm of the workday — passes a hundred clues without seeing them. Albany keeps its history close. It hides in plain sight — in the stonework underfoot, in a bricked-up doorway, in a tunnel sealed and left off the map. This city wasn’t just built — it was layered, rebuilt, forgotten, and built again. Its past lingers not in grand monuments but in the details left behind — clues for anyone willing to stop and look.

For as long as there has been an Albany, there have been rumors of what runs beneath it.

Merchants once moved their wares through cellar doors and cut-stone alleys, ducking past the dangers of crowded colonial streets. Later came smugglers, bootleggers, and the quiet operators of the Underground Railroad — slipping human lives past danger the same way whiskey moved past the law.

By the time Prohibition wrapped its grip around the city, the stories had hardened: speakeasies, trapdoors, passageways cut beneath the bars and boarding houses of the South End. Routes that allowed those with the right connections to vanish into the earth and reappear blocks away — untouched by the law or their rivals.

Little of it was written down. That was the point.

Albany’s underground grew stranger in the Cold War years. Around the Capitol — in the shadow of state power — rumors spread of fortified tunnels, stocked supply rooms, and government safe zones buried beneath layers of marble and politics. Emergency escape routes for officials.

During Governor Nelson Rockefeller's tenure, a secure bunker was constructed beneath the New York State Executive Mansion, connected by a tunnel and designed to protect the governor in times of crisis. Over time, this space was repurposed and now serves a more mundane role — but its presence adds to Albany's layered history of preparedness and secrecy.

Restoration Obscura is where lost history comes back to life — in words, in images, and in the forgotten places still waiting to be found. These stories aren’t scraped from Wikipedia. They’re dug from the archives, walked in the field, and told with care.

If you believe the past still matters — if you believe in slowing down, looking closer, and preserving what time tries to erase — I hope you’ll join me here.

Subscribe to support independent, reader-powered history. Get every story delivered straight to you.

Not far away, at the W. Averell Harriman State Office Building Campus, a two-story underground bunker was built near the State Police Headquarters. Originally constructed during the Cold War to ensure the continuity of New York State's government in the event of nuclear attack, it could once accommodate 400 people for up to two weeks. Renovated in the 1990s for the State Emergency Management Office, the facility has been activated during major events like the Y2K transition, 9/11, and Hurricanes Irene and Sandy. Fallout provisions cached deep below Empire State Plaza.

One of the most well-known — and least mysterious — of these tunnels is simply called "The Subway." It runs beneath West Capitol Park, connecting the New York State Capitol building with the Alfred E. Smith Building. Official, utilitarian, and built for practicality rather than secrecy, the Subway nonetheless feeds the city's long fascination with its underground. It is a reminder that not all tunnels are the stuff of rumor — some are simply built to keep the machinery of government moving, even in the worst of times.

Another integral part of Albany's underground is the Empire State Plaza’s vast subterranean concourse — sometimes called Albany's "Underground City." Built during Governor Nelson Rockefeller's sweeping urban renewal projects, this system connects state buildings, shops, and offices, allowing workers to move throughout the complex without setting foot outside.

Further from the Capitol, the Central Avenue pedestrian tunnels in Colonie tell their own story. Originally constructed to allow safe passage beneath one of the city's busiest corridors, these tunnels have since been repurposed for utility access. The entrances may be sealed, but the structures — hidden in plain sight — remain.

Albany's legacy in the Underground Railroad is also carved into the built environment. The Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence in Arbor Hill, still standing today, served as a critical stop for freedom seekers moving north. The home offers a rare, tangible connection to the city's clandestine past — a past shaped by tunnels, basements, and passageways built for survival.

Today, the most visible parts of Albany’s underground are pedestrian — the sterile tunnels beneath the modern government complex, connecting offices like arteries beneath stone skin. The University at Albany has its own system — low-ceilinged, concrete corridors built to ferry students through brutal winters — but the stories told about them stretch far beyond utility. Originally designed to house heating, cooling, and communications infrastructure, these tunnels have become part of campus lore — a built environment that hums with unseen energy.

What remains of the older tunnels — the human-scaled ones, the ones built for danger — survives mostly in rumor.

There are said to be passageways beneath the Palace Theatre. Another beneath Central Avenue, where a long-lost entrance was photographed years ago before it was sealed or erased. In the South End and Arbor Hill, stories persist of basements with false walls, of crawl spaces that once sheltered freedom seekers headed north.

These are Albany’s ghost routes. Their maps are memory. Their guides are the last voices that remember.

No official blueprint survives of the city’s full underground. What is left belongs to those who know where to look — or who were shown, once, in trust or necessity.

But even now — in forgotten corners of Albany’s older neighborhoods — there are marks. Iron gates fused with rust. Bricked archways in basement walls. Stairwells that descend into darkness but lead nowhere a building inspector cares to list.

Albany keeps its secrets well.

And perhaps this is as it should be. There is something profoundly human about the need for tunnels — for hidden passageways. The instinct to dig beneath the world we know is ancient and unyielding. It speaks not only to fear or flight but to longing — to the dream of moving unseen, of slipping away from the known world into quiet earth. Tunnels are not only routes of escape; they are places of transformation. They are thresholds between safety and danger, between the familiar and the unknown.

In this way, the forgotten arteries of Albany are not merely relics — they are the quiet evidence of who we have always been: a species drawn to shelter, to secrecy, to the instinct of building unseen worlds beneath our own. Tunnels are not acts of rebellion or defiance — they are acts of preservation. They exist because something precious needed protecting — life, memory, escape, or simply a way forward in uncertain times. Long after surface streets are repaved and skylines are remade, these hollowed spaces endure — patient, silent, holding the outlines of lives once lived and the choices people made when the surface world could not hold them.

What is Restoration Obscura?

The name Restoration Obscura is rooted in the early language of photography. The camera obscura—Latin for “dark chamber”—was a precursor to the modern camera, a box that transformed light into shadow and shadow into fleeting image. This project reverses that process. Instead of letting history fade, Restoration Obscura brings what’s been lost in the shadows back into focus.

But this is more than photography. This is memory work.

Restoration Obscura blends archival research, image restoration, investigative storytelling, and historical interpretation to uncover stories that have slipped through the cracks—moments half-remembered or deliberately forgotten. Whether it's an unsolved mystery, a crumbling ruin, or a water-stained photograph, each piece is part of a larger tapestry: the fragments we use to reconstruct the truth.

History isn’t a static timeline—it’s a living narrative shaped by what we choose to remember. Restoration Obscura aims to make history tactile and real, reframing the past in a way that resonates with the present. Because every photo, every ruin, every document from the past has a story. It just needs the light to be seen again.

If you enjoy stories like these, subscribe to Restoration Obscura on Substack to receive new investigations straight to your inbox. Visit www.restorationobscura.com to learn more.

You can also explore the full archive of my work at www.johnbulmermedia.com.

Every Photo Has a Story.

© 2025 John Bulmer Media & Restoration Obscura. All rights reserved.

Content is for educational purposes only.

Permissions Statement

Restoration Obscura may not hold copyright for all images featured in its archives or publications. For uses beyond educational or non-commercial purposes, please contact the institution or original source that provided the image.