A View from the Lantern Room

Restoration Obscura's Field Guide to the Night Chapter Preview: Lighthouses Along the Hudson

The latest episode of the Restoration Obscura Field Guide Podcast, exploring the hidden nuclear silos of the Adirondacks, is now available on all major streaming platforms.

Long before radar or satellites, before coastlines were charted or compasses widespread, ancient civilizations raised towers of stone and lit them with open flame. These early lighthouses, beacons of fire on headlands and islands, marked danger, welcomed travelers, and held back the chaos of unlit waters. In Egypt, Greece, and Rome, fire became signal, transforming darkness into meaning. Across centuries, night shaped how we moved, how we built, and how we survived. Today, that relationship is fading. Restoration Obscura’s Field Guide to the Night is a call to remember. This abridged chapter preview, drawn from a larger work that spans Cold War skies, blackout cities, radio towers, and aurora storms, explores the Hudson River’s historic lighthouses as one of many ways we once lived with the dark rather than pushed it away. Fire lit our way for millennia, now we drown it in artificial glare. If you feel the cost of that loss, this book is for you. Order now and reclaim your connection to the night.

The Hudson River has long served as a vital artery for commerce, transport, and cultural exchange, stretching from the harbors of New York City deep into the interior of the state. Its tidal reach and relative navigability made it a natural thoroughfare for Indigenous peoples long before the arrival of Dutch and English traders. By the early nineteenth century, that role had expanded dramatically. The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 and the Delaware and Hudson Canal in 1828 transformed the river into the central spine of a continental trade network. Goods from the American heartland and coal from Pennsylvania flowed toward Manhattan and beyond, while manufactured wares and urban luxuries moved upstream into newly connected frontier towns.

This increase in traffic brought new dangers. The Hudson, though picturesque, was never a gentle corridor. Its lower half is a tidal estuary, subject to surging currents and shifting shallows. Treacherous shoals, submerged rocks, and fog-bound narrows could easily wreck a vessel or ground a barge. River pilots understood the hazards in a way that was both professional and personal. Some carried those lessons in stories of wrecked sloops and grounded packets. Others bore them in the scars of old collisions or the memory of lost crewmates. Progress on the water required more than mechanical ingenuity. It depended on visibility.

In the 1820s, lighthouses began to rise along the river’s edge. These were working structures, squat, often octagonal, built of brick or stone, and shaped by the daily demands of inland navigation. Roughly a dozen would come to operate along the Hudson’s length. Each stood in response to a specific threat. Each had keepers, often solitary or joined by family, who maintained the lamps, trimmed the wicks, and kept the watch through long, dark hours.

Today, seven of these historic lighthouses remain under active preservation. Some still shine with solar-powered lamps. Others remain dark, their Fresnel lenses removed, their towers visited only by maintenance crews or occasional tourists. The Statue of Liberty briefly functioned as a lighthouse from 1886 to 1902. Its beam never achieved maritime effectiveness, but the effort remains a historical footnote at the river’s mouth.

These structures have outlasted their original purpose. They have become symbols of identity. Preserved through local effort, they reflect both the region’s industrial ascent and the quiet relationship between riverside communities and the waters that shaped them.

Origins of the Beacons

The need for Hudson River lighthouses grew slowly, built on experience and hardship. Early navigation relied on the landscape and the practiced eyes of those who traveled it. As steamboats, canal boats, and long-haul barges crowded the waters, instinct gave way to precision. With every wreck, every grounding, every missed turn in the fog, the call for fixed lights grew louder.

In the 1820s, Congress began appropriating funds for inland navigation infrastructure. The Hudson was among the earliest beneficiaries. Stony Point Lighthouse rose in 1826 on high ground above Haverstraw Bay. Its purpose was to help distinguish the rocky headland from the surrounding hills, especially in thick weather. Other lights followed. Esopus Meadows warned of a shifting channel near the river’s center. Sleepy Hollow stood near shoals infamous for grounding vessels. These lighthouses were built where argument, incident, and community petition made the case. They were placed where human error had already paid the price.

Their designs reflected both regional conditions and federal trends. Octagonal stone towers, cast iron cylinders, mansard roofs, and clapboard siding were chosen to resist fire, ice, and neglect. Some towers replaced earlier lights lost to erosion or storm damage. Others borrowed their plans from coastal structures as part of an effort to standardize public works.

Each lighthouse became a kind of threshold. They marked places where safety began, where guidance resumed, and where effort reached its destination. These were working buildings, built to last and built to matter.

The Surviving Lighthouses

Jeffrey’s Hook Lighthouse

Popularly known as the "Little Red Lighthouse," this small cast-iron structure once stood at Sandy Hook, New Jersey. In 1921, it was moved to Manhattan’s northern edge beneath the newly constructed George Washington Bridge. Decommissioned in 1948, it might have vanished entirely were it not for the 1942 children’s book that carried its story into classrooms across the country. Public outcry, led largely by schoolchildren, helped preserve it.

Sleepy Hollow Lighthouse

Also known as Tarrytown Light, this sparkplug-style structure was built in 1883 and originally stood offshore. Land reclamation from the nearby General Motors plant has since brought the shore to its doorstep. The lighthouse was automated in 1957 and decommissioned in 1961. A recent restoration project in 2024 returned it to its 1937-era condition, including interior details lost to time.

Stony Point Lighthouse

The oldest lighthouse on the Hudson River, Stony Point was completed in 1826. It was designed to help ships navigate the rocky bluff above Haverstraw Bay. Nancy Rose served as keeper here for nearly five decades. During one particularly dense fog, she rang the lighthouse bell by hand for 56 straight hours. In 1903, she reportedly fought off an intruder with a fireplace poker. Her long service and quiet bravery became part of the lighthouse’s legend.

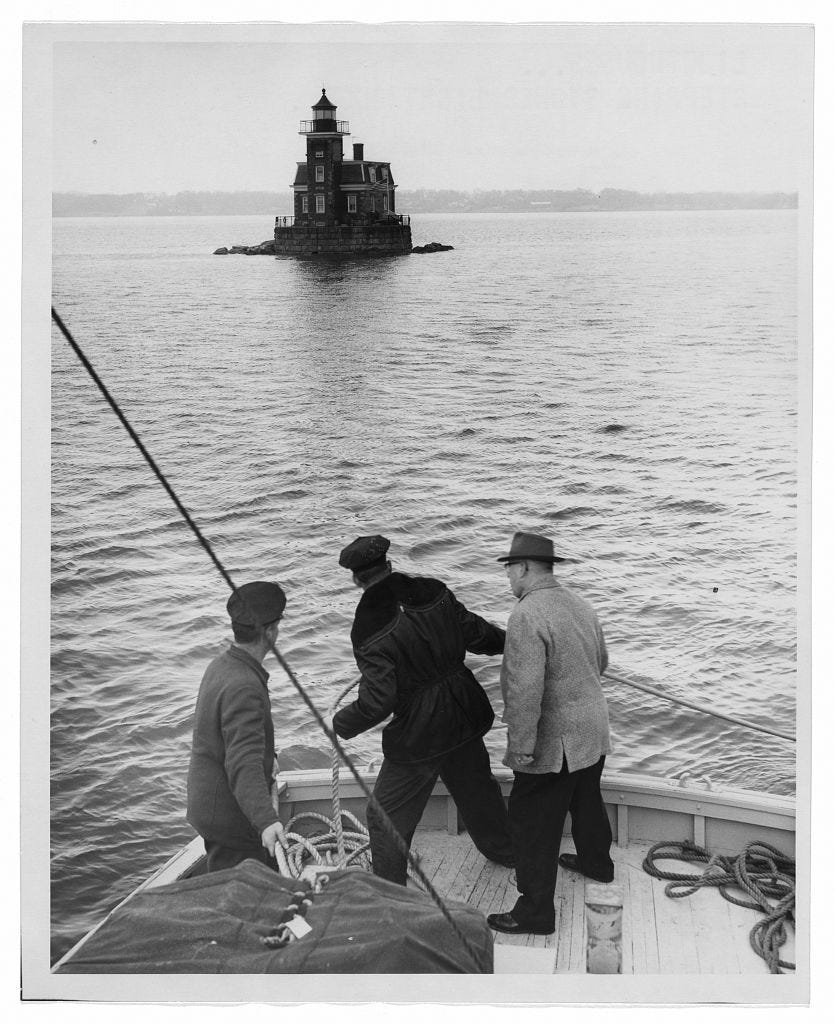

Esopus Meadows Lighthouse

Built in 1871 on piles driven into the river’s center, this wooden lighthouse replaced an earlier structure destroyed by ice in 1838. Known as the “Maid of the Meadows,” it served until automation in 1965. The structure sat abandoned for decades before being restored and re-lit in 2003. Life on station was often lonely. One keeper shared his quarters with a rooster and two de-scented skunks. In 1949, a body washed ashore nearby and was never identified.

Rondout Lighthouse

Located at the mouth of Rondout Creek, this brick tower was completed in 1915. It replaced earlier wooden structures and remains active today. After automation, it was neglected for years. The lighthouse is linked to the “Widow’s Watch” legend, which may have roots in the death of a groom on his wedding night and echoes in the life of Catherine Murdock, who took over after her husband George drowned in 1857.

Saugerties Lighthouse

This sturdy brick lighthouse was built in 1869 at the confluence of Esopus Creek and the Hudson. It replaced earlier lights destroyed by fire and ice. Abandoned after automation in 1954, it faced demolition during the 1960s. A local historian and architect organized a preservation campaign that saved the building. One keeper reportedly died here during a harsh winter when no medical help could reach him in time.

Hudson–Athens Lighthouse

Completed in 1874, this mid-river lighthouse was built with a bow-shaped base to deflect ice. It was automated in 1949 and remains in operation. Structural instability led to its listing in 2024 among America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. Local stories tell of a keeper who vanished while rowing to the station. The surrounding waters are notorious for shipwrecks, some involving livestock swept away from overturned barges.

Statue of Liberty

From 1886 to 1902, the Statue of Liberty briefly operated as a lighthouse. Its electric arc lamp was too dim and unfocused to serve practical navigation. Though unsuccessful in that role, it holds a unique place in the history of Hudson River beacons.

Keepers and Legends

Within each lighthouse lived people who carried the burden of vigilance not by shift, but by season, year, and lifetime. The keeper’s role was not glamorous. It was relentless. These individuals endured solitude, weathered hardship, and committed themselves to a pattern of labor dictated by fog, tide, and flame. Nancy Rose at Stony Point, Jacob Ackerman at Sleepy Hollow, and Catherine Murdock at Rondout are remembered not only for their tenure, but for the resilience they embodied. Their lives became part of the structures they maintained.

Nancy Rose served for forty-seven years at Stony Point, walking the worn spiral of stairs with firewood in her arms and worry on her shoulders. She kept a fog bell ringing for fifty-six hours straight during a maritime crisis, using nothing but strength and stubborn resolve. Her later encounter with an intruder—repelled with nothing more than a fireplace poker—became local legend. Those who followed her whispered stories of her footsteps echoing in empty rooms, as if the tower itself remembered her rhythm.

Jacob Ackerman, the first keeper of the Sleepy Hollow Light, saved at least nineteen lives during his years of service. He knew the current and the shoals like a second language. His reputation for vigilance made him a figure of quiet authority in the local community. For passing vessels, his signal was a promise—someone was watching.

Catherine Murdock’s story at Rondout began in loss. When her husband, George, drowned in 1857, she stepped into his role and never left. She raised her children within the keeper’s quarters, maintained the beacon into her seventies, and kept the light burning through storm, illness, and age. In her journals, the tasks were modest but relentless: polishing lenses, trimming wicks, recording the wind. The lighthouse was her station, her sanctuary, and her statement of endurance.

John Kerr at Esopus Meadows lived a quieter tale. His journals note the company of a rooster and two de-scented skunks, kept for companionship through long winters. He shoveled snow from the catwalk, logged barometric pressure, and wrote letters by lamplight while ice cracked around the pilings. His animals were not novelty—they were insurance against a kind of loneliness too deep for language.

From these routines, stories grew. At Rondout, the “Widow’s Watch” was said to appear in the upper windows during storms, a silhouette pacing in sorrow. At Stony Point, visitors claimed to hear footsteps on stairwells long sealed. At Esopus Meadows, lights flickered in the fog even after the beacon was darkened. These were not ghost stories in the typical sense. They were echoes of labor and presence. Solitude became memory. Memory took the shape of narrative. The keepers never truly left. They became part of the structure, stitched into its mortar by repetition, watchfulness, and resolve.

Preservation and Cultural Memory

The survival of these towers was never guaranteed. After automation, many stood abandoned. Roofs sagged, lenses disappeared, windows shattered. The purpose was gone, and for a time, so was the will to preserve. Yet the lighthouses endured because people made the decision that they should. They were saved by volunteers, local historians, and quiet coalitions of citizens who understood that history is not a passive inheritance. It is a choice we make to carry forward.

Groups like the Saugerties Lighthouse Conservancy, the Save Esopus Lighthouse Commission, and the Hudson-Athens Lighthouse Preservation Society did more than raise money. They rebuilt catwalks and hauled lumber by hand. They navigated bureaucracies, filed restoration permits, secured insurance, and negotiated with state agencies. They stood in leaking towers and asked themselves if memory was worth the work. Then they got to work.

Some volunteers came from maritime families. Others arrived with no direct tie to the river but felt its call just the same. Their motivation varied, but their outcome was the same. They treated rust and rot with patience. They stabilized foundations. They wrote grant proposals by candlelight inside towers that hadn’t been lit in decades.

Through their effort, lighthouses that once belonged to federal navigation systems became something more intimate. They became living artifacts. Visitors today walk through these towers and see them not as relics, but as extensions of place. A lighthouse is no longer only a beacon. It is a classroom, a museum, a quiet place to witness time. It anchors local identity to the physical world. It offers continuity in a landscape that often forgets.

Shining On

Hudson River lighthouses once lit the way through fog and darkness. That was their design. But their legacy reaches further. Today, these towers illuminate something more human: the endurance of quiet labor, the dignity of forgotten roles, and the profound effect of care taken in public service.

Their survival into the present is the result of effort, not chance. These lighthouses stand today because individuals decided they were worth saving. The process was slow. It involved thousands of small actions—replacing glass, hauling timber, submitting grant paperwork, organizing tours, sharing stories. These were working buildings once, and they remain working legacies. Each one reflects a decision to preserve something real, useful, and quietly important. They shine because people chose to keep them lit.

Discover Restoration Obscura’s Field Guide to the Night by John Bulmer

A hauntingly beautiful journey through how darkness has shaped human history, culture, and memory, from wartime blackouts and Cold War surveillance to ancient skywatchers and light‑polluted nights. Part memoir, part cultural history, this immersive field guide challenges us to step out of the glow and reconnect with what the night still has to teach.

📚 Paperback ($14.99) / Kindle ($9.99) | 368 pages | Published June 1, 2025 | ISBN 979‑8218702731 | Restoration Obscura Press

Available worldwide on Amazon (Prime eligible)

Sources and Suggested Further Reading

Bulmer, John. Restoration Obscura’s Field Guide to the Night. Restoration Obscura Press, 2025. A comprehensive exploration of the human relationship with darkness across history, science, folklore, and infrastructure. This book blends cultural memory with investigative narrative, featuring extended chapters on Hudson River lighthouses, Cold War surveillance systems, blackout cities, firewatch towers, and auroral phenomena. www.restorationobscura.com

United States Coast Guard Historian’s Office – Tarrytown Lighthouse, Hudson River, New York. https://www.history.uscg.mil

LighthouseFriends.com – Entries on Jeffrey’s Hook, Esopus Meadows, Rondout, Stony Point, and Hudson–Athens Lighthouses. https://www.lighthousefriends.com

Hudson River Lighthouses – Hudson River Maritime Museum. https://www.hudsonriverlighthouses.org

National Park Service – The Statue of Liberty as a Lighthouse, 1886–1902. https://www.nps.gov/stli/learn/historyculture/statue-as-lighthouse.htm

Scenic Hudson – “Why Each Enduring Hudson River Lighthouse Is So Special.” https://www.scenichudson.org/viewfinder

Hudson River Maritime Museum – Keeper logs, oral histories, and preservation records. https://www.hrmm.org

Esopus Meadows Lighthouse Alliance – Restoration history and community engagement. https://www.esopusmeadowslighthouse.org

Saugerties Lighthouse Conservancy – Historical information and overnight stays. https://www.saugertieslighthouse.com

National Trust for Historic Preservation – 2024 America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. https://savingplaces.org

NOAA Office of Coast Survey – Historical Charts of the Hudson River. https://www.nauticalcharts.noaa.gov

Lighthouse Digest – Keeper profiles, maritime folklore, and lighthouse preservation. https://lighthousedigest.com

The Fresnel Lens – Articles on lighthouse optics and Hudson Valley beacons.

https://www.thefresnellens.com

New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation – Lighthouse registry and restoration reports. https://parks.ny.gov

About Restoration Obscura

Restoration Obscura is where overlooked history gets another shot at being seen, heard, and understood. Through long-form storytelling, archival research, and photographic restoration, we recover the forgotten chapters—the ones buried in basements, fading in family albums, or sealed behind locked doors.

The name nods to the camera obscura, an early photographic device that captured light in a darkened chamber. Restoration Obscura flips that idea, pulling stories out of darkness and casting light on what history left behind.

This project uncovers what textbooks miss: Cold War secrets, vanished neighborhoods, wartime experiments, strange ruins, lost towns, and the people tied to them. Each episode, article, or image rebuilds a fractured past and brings it back into focus, one story at a time.

If you believe memory is worth preserving, if you’ve ever felt something standing at the edge of a ruin or holding an old photograph, this space is for you.

Subscribe to support independent, reader-funded storytelling: www.restorationobscura.com

🎧 The Restoration Obscura Field Guide Podcast is streaming now on all major streaming platforms.

Every photo has a story. And every story connects us.

© 2025 John Bulmer Media & Restoration Obscura. All rights reserved. Educational use only.

Permissions Statement

Restoration Obscura may not hold copyright for all images featured in its archives or publications. For uses beyond educational or non-commercial purposes, please contact the institution or original source that provided the image.